Em Busca de Genialidades Perdidas/ In Search of Lost Ingenuities

- luaemp

- 4 de jan.

- 16 min de leitura

(Followed by the English version)

(Ilustração de Édouard Riou)

Quando se começa a “cavar”, é certo sabido que podemos não encontrar o pote de ouro, mas encontramos coisas deliciosas de gente que por necessidade ou mero acaso, deram à luz invenções extraordinárias.

Se vos perguntar o que é que o presidente da Royal Society e fundador do que viria a ser o British Museum, tem a ver com o leite achocolatado, provavelmente vocês responderiam: nada.

Mas tem, e muito.

Hans Sloane, médico nascido em Killyleagh, no condado de Down, no longínquo ano de 1660, foi o responsável por transformar o cacau numa bebida digna de repetir. Durante uma estadia na Jamaica, onde servia como médico pessoal do governador, Sloane deparou-se com o hábito local de beber cacau misturado com água quente — uma combinação que, segundo ele, tinha o sabor de remédio amargo e textura de castigo.

Determinou, portanto, que aquilo podia (e devia) ser melhorado. Substituiu a água por leite, experimentou, gostou — e trouxe a receita consigo para Londres.

A sua intenção era medicinal — recomendava a bebida como tónico revigorante —, mas o mundo agradeceu-lhe de outra forma: nasceu o leite com chocolate, tal como o conhecemos.

Curiosamente, um médico sério, de bata e esteto, trouxe-nos algo que ninguém pediu e que todos agradecemos: o leite com chocolate.

Um pequeno acaso que acabou por adoçar o mundo…

A próxima invenção que vos trago, nasceu, pelo contrário, da necessidade ou urgência.

O Dr. Francis Rynd, cirurgião do Meath Hospital, em Dublin, viu-se, em 1844, perante um dilema nada académico: uma paciente atormentada por neuralgia facial há meses, sofrendo dores lancinantes que nenhum tratamento conseguia aliviar.

Na altura, os médicos dispunham de poucas opções eficazes — e administrar medicamentos directamente nos tecidos era impensável. Mas Rynd, cansado de ver a doente sofrer, decidiu improvisar.

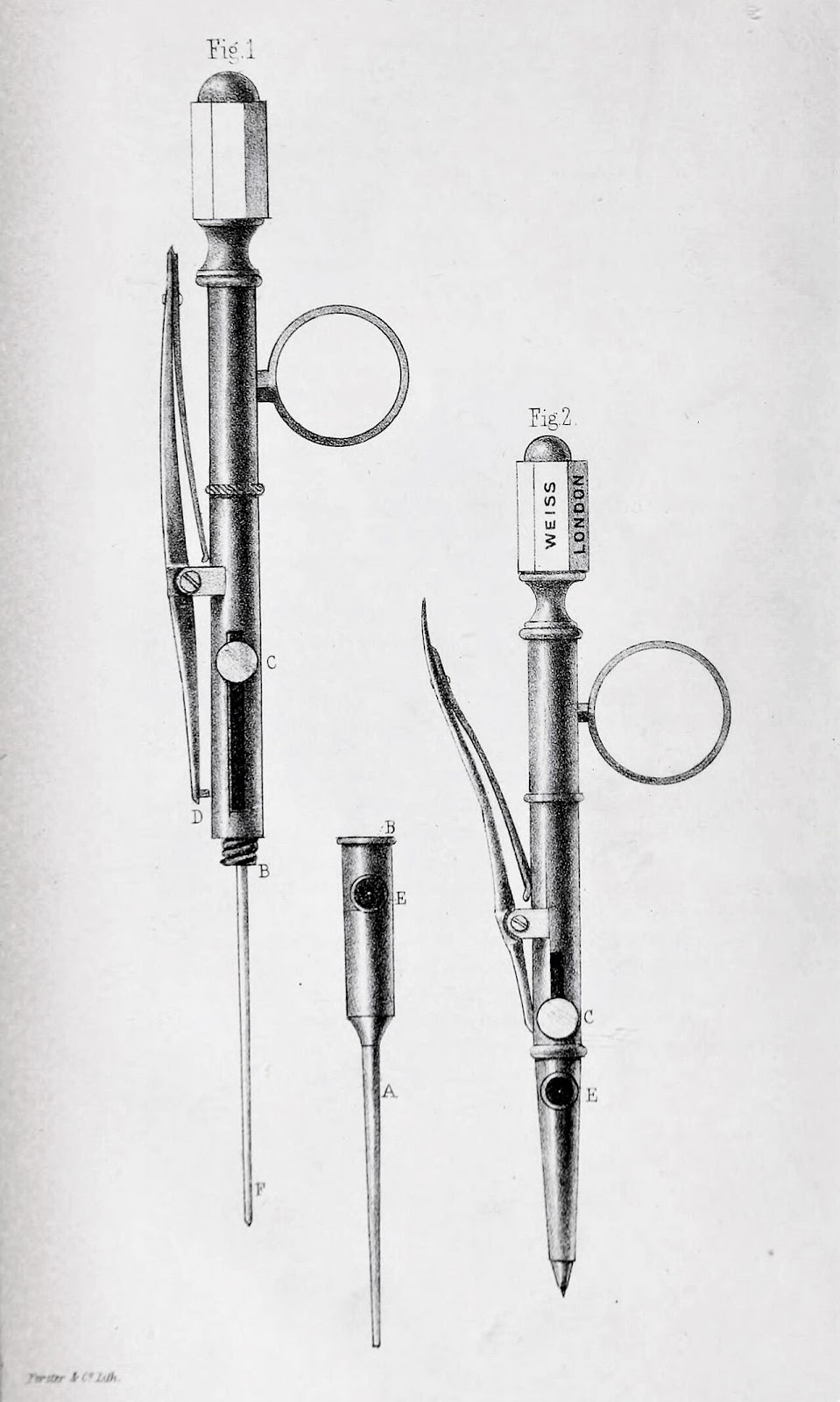

Pegou num trocarte — uma espécie de agulha oca com ponta afiada — e deixou escorrer lentamente uma solução de acetato de morfina misturada com creosoto, exactamente sobre os nervos afectados.

(Trocarte — Illustration of Rynd's hypodermic needle)

Também na medicina, mas sem tanto desespero, Arthur Leared, natural do condado de Wexford, era médico formado no Trinity College e tinha grande interesse em melhorar a prática clínica. Em 1851, desenvolveu o estetoscópio binaural, aprimorando o primeiro estetoscópio inventado pelo francês René Laennec em 1816.

Antes de Leared, os estetoscópios eram monoculares: um único tubo apoiado no peito do paciente para ouvir os sons internos do coração e dos pulmões. Funcionava, mas tinha limitações — pouco conforto, precisão reduzida e dificuldades em auscultar sons mais subtis.

Leared introduziu dois tubos, um para cada ouvido do médico, permitindo ouvir som estéreo e melhorando drasticamente a percepção de batimentos cardíacos, respiração e sopros pulmonares.

(Imagem retirada de libfocus)

A diferença era enorme: com os dois ouvidos, conseguia-se distinguir com mais clareza sons diferentes, aumentando a precisão do diagnóstico. Embora hoje se usem materiais e tecnologias mais avançadas, a lógica básica de ouvir com os dois ouvidos mantém-se nos estetoscópios modernos.

Enquanto alguns inventores se entretinham com leite achocolatado, injecções e estetoscópios, John Philip Holland, do Condado de Clare, tinha a cabeça mergulhada — literalmente — no mar. Desde jovem, a ideia de construir um navio que pudesse navegar debaixo de água fascinava-o. Em 1873, emigrou para os Estados Unidos, levando consigo essa obsessão — e foi lá que encontrou o terreno e o apoio certos para a pôr à prova.

Com financiamento de um grupo de nacionalistas irlandeses conhecidos como os Fenians, Holland construiu, em 1881, o Fenian Ram — um protótipo de submarino que parecia saído de um romance visionário. Ironia histórica: um engenheiro irlandês a criar, em solo americano, uma arma pensada para desafiar a Marinha Britânica.

O Fenian Ram era surpreendentemente avançado para o seu tempo: movido por um motor de combustão interna a querosene e equipado com sistemas de ar comprimido que lhe permitiam manobrar e submergir de forma controlada — algo quase impensável no século XIX. Embora nunca tenha sido usado em combate, serviu como protótipo crucial que permitiu a Holland experimentar e aperfeiçoar conceitos fundamentais. De qualquer forma encontra-se no Paterson Museum, em Nova Jersey, onde permanece em exibição até hoje

Mais tarde, Holland aperfeiçoaria o conceito, culminando na construção do USS Holland (SS-1), o primeiro submarino oficialmente aceite pela Marinha dos Estados Unidos, a 12 de outubro de 1900. Um homem com a cabeça no mar e os pés firmemente na história.

Se uns olhavam para a água, outros viam estrelas. Meio século antes, houve alguém fascinado por uma outra grandeza: William Parsons, 3.º Conde de Rosse, (1800-1867) no condado de Offaly, decidiu que o céu merecia uma janela maior.

No seu castelo em Birr, construiu, em meados do século XIX, o Leviatã de Parsonstown — um telescópio gigantesco, com um espelho de 1,8 metros de diâmetro, o maior do mundo durante mais de setenta anos. Parsons, essencialmente autodidacta, moldou e poliu o espelho com a sua equipa, inventando mecanismos de suporte e rotação que permitiam manobrar aquele colosso com suavidade. O resultado foi mais do que uma façanha de engenharia — foi uma revolução na astronomia. Através do Leviatã, Parsons foi o primeiro a observar e a desenhar claramente a estrutura espiral de várias nebulosas, como a do Redemoinho, revelando que essas manchas difusas no céu eram, afinal, galáxias inteiras. Se o telescópio já era um instrumento fascinante, imaginem o que este aperfeiçoamento veio revolucionar: escancarou janelas ao olhar humano, abriu caminho à astronomia extragaláctica e ampliou profundamente a compreensão da estrutura do universo. Não é à toa que o Leviatã, que veio revelar a estrutura espiral de nebulosas — que até então pareciam apenas manchas difusas —, seja considerado uma maravilha científica do século XIX, admirado por astrónomos de toda a Europa, inspirando-os a perscrutar o céu como nunca antes e abrindo caminho a uma nova visão do cosmos, com um impacto técnico e científico que viria a fundamentar os aperfeiçoamentos de telescópios até aos nossos dias.

Mais “terra a terra”, Harry Ferguson, do Condado de Down, Irlanda do Norte, mecânico autodidata e inventor, patenteou em 1926 o sistema Ferguson, revolucionando os tractores com suspensão hidráulica e controle de implementos. De repente, máquinas complicadas e perigosas podiam puxar, levantar e manobrar ferramentas com segurança e precisão, mudando para sempre a agricultura em todo o mundo.

A sua inovação tornou-se a base dos tractores modernos e deu origem à marca Massey Ferguson, sinónimo de potência, eficiência e engenho irlandês — um homem que transformou o pó e o barro em progresso.

Porém, saibam que não tendo sido ele o inventor do monoplano, foi o primeiro irlandês a construir e voar a sua própria aeronave deste tipo, provando que para ele não havia limites entre terra e céu.

John Joly (1857–1933), nascido em Holywood, condado de Offaly, foi um dos mais destacados cientistas irlandeses do seu tempo. Formado em Engenharia Civil pelo Trinity College Dublin em 1882, Joly combinava investigação académica com aplicações práticas inovadoras. Todos sabemos que, nessa época, o conhecimento não era estanque — isto é, não se confinava a uma única área — mas Joly exagerou um bocadinho.

Curiosamente, não foi por nenhuma invenção em engenharia civil que ficou na história. As suas contribuições marcantes seriam em física, com o desenvolvimento do fotómetro de radiação, um dos primeiros instrumentos capazes de medir com precisão a intensidade da luz solar; na geologia, ao calcular a idade da Terra utilizando desde a salinidade dos oceanos até técnicas de radioatividade; e na medicina, como pioneiro da radioterapia com o chamado “método de Dublin”, que aplicava radiação directamente nos tumores, precursor de muitas terapias modernas.

O seu trabalho inovador valeu-lhe a eleição como membro da Royal Society em 1892 e a Medalha Real em 1910, reconhecimento internacional de um cientista cuja visão ultrapassava fronteiras. Um verdadeiro polímata, combinava talento e visão científica, mostrando que, mesmo no século XIX, os irlandeses olhavam para o mundo em grande escala — e ajudavam a iluminá-lo, literalmente, deixando um legado que continua a influenciar a geologia, a física e a medicina.

O engenheiro irlandês Walter Gordon Wilson, de Dublin, decidiu que a guerra precisava de rodas mais ousadas — ou melhor, de lagartas. Após vários esboços e muitas folhas de papel deitadas ao lixo, colaborou, em

1915, com Sir William Tritton na criação do protótipo "Little Willie", — nome estranho, mas enfim —, o primeiro tanque de guerra funcional, projectado para atravessar trincheiras e terrenos difíceis durante a Primeira Guerra Mundial. Embora rudimentar, essa invenção marcou o início da mecanização dos campos de batalha. O "Little Willie" foi o primeiro protótipo de tanque a ser construído, embora tenha sido rapidamente superado por modelos posteriores. Este desenvolvimento pioneiro abriu caminho para a evolução dos blindados modernos.

Numa postura de salvamento em vez de destruição, James Francis Partridge, natural do Condado de Down, na Irlanda do Norte, revolucionou a medicina de emergência em 1965 ao desenvolver o primeiro desfibrilhador portátil. Antes dele, os desfibrilhadores eram máquinas pesadas e restritas a hospitais, limitando o tratamento de paragens cardíacas a profissionais dentro de portas.

Partridge imaginou um dispositivo compacto, transportável, que pudesse ser usado por paramédicos e médicos fora do hospital — literalmente, levar a vida de volta às mãos de quem estava na rua. A sua invenção permitiu intervir rapidamente em situações críticas, aumentando drasticamente as hipóteses de sobrevivência de pacientes em paragem cardíaca.

Salvar vidas deixou de depender apenas de chegar a tempo ao hospital; agora, o poder de reiniciar um coração podia viajar junto com a ambulância. Um exemplo brilhante de engenho irlandês com impacto directo no quotidiano de milhões de pessoas.

Vincent Barry é outra figura realmente notável, e curiosamente pouco falada, mesmo na própria Irlanda.

Este homem, nascido no condado de Cork, foi um químico que dedicou a vida à investigação científica com um impacto global. Trabalhou no Instituto de Investigação Médica da Irlanda (IMRI), onde na década de 1950, liderou uma equipa de cientistas empenhada em encontrar uma cura para a tuberculose — uma das grandes preocupações médicas da época.

Mas, como tantas vezes acontece em ciência, o universo tinha outros planos:

o verdadeiro achado veio por acaso: durante essas experiências, a equipa descobriu um composto chamado B663, que se revelou extraordinariamente eficaz contra a lepra — uma doença que ainda devastava comunidades em várias partes do mundo.

Esse composto ficou mais tarde conhecido como clofazimina, e viria a ser adoptado no início da década de 1960 como parte essencial do tratamento contra a lepra, sendo oficialmente incorporado nas recomendações da Organização Mundial de Saúde em 1981 — e ainda hoje em uso.

Graças a esse avanço, centenas de milhares de pessoas foram curadas ou deixaram de ser isoladas socialmente — um feito que, curiosamente, nasceu num laboratório irlandês modesto e longe dos grandes centros de investigação internacionais.

Ernest Walton (1903–1995), natural de Waterford, não foi apenas mais um físico: foi o pioneiro da física nuclear. Em 1932, ao lado de John Cockcroft, conseguiu separar o núcleo de um átomo de lítio, lançando partículas a grande velocidade contra ele — algo que nunca tinha sido feito antes. Para isso, construíram o gerador Cockcroft–Walton, um tipo de acelerador de partículas linear que acelerava partículas até colidirem com o átomo, libertando energia e abrindo um mundo totalmente novo. O feito parecia quase mágico: de repente, os átomos, antes invisíveis e impenetráveis, podiam ser manipulados, estudados e compreendidos. Em 1951, Walton e Cockcroft receberam o Prémio Nobel da Física, reconhecimento merecido por uma experiência que mudou a história da ciência, abrindo portas para a física nuclear. Mas o verdadeiro impacto de Walton não se ficou por prémios ou laboratórios: deixou uma marca duradoura na ciência, inspirando novas gerações e provou que, mesmo num país pequeno, se podia desvendar os segredos mais profundos da matéria.

A lista é interminável e, quanto mais “cavo”, mais genialidade encontro… Por momentos até me parece que já cheguei ao centro da Terra. Mas os inventos sucedem-se e não me admiraria que, com tanta escavação, acabasse por perfurar a superfície… Melhor ficar por aqui, antes que todos sejamos desintegrados no espaço.

English version

When one begins to “dig,” it is well known that one might not find the pot of gold, but one discovers delightful things created by people who, out of necessity or mere chance, brought forth extraordinary inventions.

If you were asked what the president of the Royal Society and founder of what would become the British Museum has to do with chocolate milk, you would probably answer: nothing.

But it does — and quite a lot.

Hans Sloane, a physician born in Killyleagh, County Down, in the distant year of 1660, was responsible for turning cocoa into a drink worth repeating. During a stay in Jamaica, where he served as the governor’s personal physician, Sloane encountered the local habit of drinking cocoa mixed with hot water — a combination that, according to him, tasted like bitter medicine and had the texture of punishment.

He decided, therefore, that it could (and should) be improved. He replaced the water with milk, tried it, liked it — and brought the recipe back with him to London.

His intention was medicinal — he recommended the drink as an invigorating tonic — but the world benefited in another way: chocolate milk, as we know it today, was born.

Curiously, a serious doctor, in his coat and with a stethoscope in hand, gave us something that no one asked for — and that everyone is grateful for: chocolate milk.

A small stroke of chance that ended up sweetening the world…

The next invention I bring you, by contrast, was born out of necessity or urgency.

Dr. Francis Rynd, a surgeon at Meath Hospital in Dublin, found himself in 1844 facing a highly unusual dilemma: a patient had been tormented by facial neuralgia for months, suffering excruciating pain that no treatment could relieve.

At the time, doctors had few effective options — and administering medication directly into the tissues was unthinkable. But Rynd, tired of seeing his patient suffer, decided to improvise.

He took a trocar — a kind of hollow needle with a sharp tip — and slowly allowed a solution of morphia acetate mixed with creosote to flow directly onto the affected nerves.

(Trocar — Illustration of Rynd's hypodermic needle)

The method seemed almost artisanal — and indeed it was — but it worked. Minutes later, the pain subsided, and the patient, who had not slept for weeks, finally fell asleep peacefully.

Rynd recorded the case and published it in the Dublin Medical Press in 1845. Unknowingly, he had performed the first documented subcutaneous injection in history — establishing the principle that would later inspire the modern hypodermic syringe. His instrument had neither plunger nor glass reservoir, and it didn’t even have the name “syringe,” but the idea was there: to deliver medication directly into the tissues with precision and control.

Decades later, other doctors perfected the mechanism, adding the plunger and shaping the syringe as we know it today. But it was Rynd, with a hollow tube and a bold idea, who paved the way at that precise moment when a doctor decided that pain should not wait for the perfect invention — and created it himself.

Also in medicine, but without quite so much urgency, Arthur Leared, a native of County Wexford, was a physician trained at Trinity College with a strong interest in improving clinical practice. In 1851, he developed the binaural stethoscope, enhancing the first stethoscope invented by the Frenchman René Laennec in 1816.

(Image taken from libfocus)

Before Leared, stethoscopes were monocular: a single tube placed on the patient’s chest to listen to the internal sounds of the heart and lungs. It worked, but had limitations — little comfort, reduced accuracy, and difficulty picking up subtler sounds.

Leared introduced two tubes, one for each of the physician’s ears, allowing stereo hearing and drastically improving the perception of heartbeats, respiration, and lung murmurs.

The difference was enormous: with both ears, different sounds could be distinguished more clearly, increasing diagnostic accuracy. Although modern stethoscopes now use more advanced materials and technology, the basic principle of listening with both ears remains in use today.

While some inventors were preoccupied with chocolate milk, injections, and stethoscopes, John Philip Holland, from County Clare, had his head — literally — underwater. From a young age, he was fascinated by the idea of building a vessel that could navigate beneath the sea. In 1873, he emigrated to the United States, carrying that obsession with him — and it was there that he found the right environment and support to put it to the test.

With funding from a group of Irish nationalists known as the Fenians, Holland built in 1881 the Fenian Ram — a submarine prototype that seemed straight out of a visionary novel. An historical irony: an Irish engineer, on American soil, creating a weapon designed to challenge the British Navy.

The Fenian Ram was remarkably advanced for its time: powered by a kerosene internal combustion engine and equipped with compressed air systems that allowed it to maneuver and submerge in a controlled way — almost unthinkable in the 19th century. Although it was never used in combat, it served as a crucial prototype that allowed Holland to experiment with and refine fundamental concepts. Today, it can be seen on display at the Paterson Museum, in New Jersey.

Later, Holland perfected the concept, culminating in the construction of the USS Holland (SS-1), the first submarine officially accepted by the United States Navy, on October 12, 1900. A man with his head in the sea and his feet firmly in history.

While some looked at the water, others gazed at the stars. Half a century earlier, there was someone fascinated by another kind of grandeur: William Parsons, 3rd Earl of Rosse (1800–1867), in County Offaly, decided that the sky deserved a larger window.

At his castle in Birr, in the mid-19th century, he built the Leviathan of Parsonstown — a gigantic telescope with a 1.8-meter-diameter mirror, the largest in the world for more than seventy years. Parsons, essentially self-taught, shaped and polished the mirror with his team, inventing support and rotation mechanisms that allowed the colossus to be maneuvered smoothly. The result was more than an engineering feat — it was a revolution in astronomy.

Through the Leviathan, Parsons was the first to clearly observe and draw the spiral structure of several nebulae, such as the Whirlpool Nebula, revealing that these diffuse patches in the sky were, in fact, entire galaxies. If the telescope was already a fascinating instrument, imagine what this refinement went on to revolutionize: it opened new windows to the human eye, paved the way for extragalactic astronomy, and profoundly expanded the understanding of the universe's structure.

It is no wonder that the Leviathan — which revealed the spiral structure of nebulae — was considered a 19th-century scientific marvel, admired by astronomers across Europe, inspiring them to scrutinize the sky like never before and laying the foundation for modern telescope advancements that continue to this day.

A little more down to earth, Harry Ferguson, from County Down, Northern Ireland, a self-taught mechanic and inventor, patented in 1926 the Ferguson System, revolutionizing tractors with hydraulic lift and implement control. Suddenly, complex and dangerous machines could pull, lift, and maneuver tools safely and precisely, forever changing agriculture around the world.

His innovation became the foundation of modern tractors and gave rise to the Massey Ferguson brand — a name synonymous with power, efficiency, and Irish ingenuity — a man who turned dust and mud into progress.

However, although he wasn’t the inventor of the monoplane, he was the first Irishman to build and fly his own aircraft of this type — proving that, for him, there were no limits between earth and sky.

John Joly (1857–1933), born in Holywood, County Offaly, was one of Ireland’s most distinguished scientists of his time. A Civil Engineering graduate from Trinity College Dublin in 1882, Joly combined academic research with innovative practical applications. We all know that, in those days, knowledge was not compartmentalised — that is, it wasn’t confined to a single field — but Joly took that a little further.

Curiously, it wasn’t for any invention in civil engineering that he made history. His most remarkable contributions came in physics, with the development of the radiation photometer, one of the first instruments capable of accurately measuring the intensity of sunlight; in geology, by calculating the age of the Earth using everything from ocean salinity to radioactive methods; and in medicine, as a pioneer of radiotherapy with the so-called Dublin method, which applied radiation directly to tumours — a precursor of many modern treatments.

His innovative work earned him election to the Royal Society in 1892 and the Royal Medal in 1910 — international recognition for a scientist whose vision transcended boundaries. A true polymath, he combined talent and scientific insight, showing that even in the 19th century, the Irish viewed the world on a grand scale — and helped to illuminate it, quite literally — leaving a legacy that continues to influence geology, physics, and medicine to this day.

The Irish engineer Walter Gordon Wilson, from Dublin, decided that war needed bolder wheels — or rather, tracks. After several sketches and more than a few sheets of paper sacrificed to ambition, he collaborated in 1915 with Sir William Tritton on the creation of the prototype “Little Willie” — a strange name, admittedly — the first functional battle tank, designed to cross trenches and rough terrain during the First World War.

Although rudimentary, this invention marked the beginning of the mechanisation of the battlefield. Little Willie was the first tank prototype ever built, though it was soon surpassed by later models. This pioneering development paved the way for the evolution of modern armoured vehicles.

In a stance of rescue rather than destruction, James Francis Partridge, born in County Down, Northern Ireland, revolutionised emergency medicine in 1965 by developing the first portable defibrillator. Before him, defibrillators were heavy machines confined to hospitals, limiting cardiac arrest treatment to professionals working indoors.

Partridge imagined a compact, transportable device that could be used by paramedics and doctors outside hospital walls — literally bringing life back into the hands of those on the street. His invention made it possible to act swiftly in critical situations, dramatically increasing the chances of survival for cardiac arrest patients.

Saving lives no longer depended solely on reaching the hospital in time; now, the power to restart a heart could travel with the ambulance. A brilliant example of Irish ingenuity with a direct impact on the daily lives of millions.

Vincent Barry is another truly remarkable figure — and, curiously, a rather overlooked one, even in Ireland itself.

Born in County Cork, Barry was a chemist who devoted his life to scientific research with a global impact. He worked at the Irish Medical Research Institute (IMRI), where, in the 1950s, he led a team of scientists determined to find a cure for tuberculosis — one of the major medical concerns of the time.

But, as so often happens in science, the universe had other plans.

The real breakthrough came by chance: during those experiments, the team discovered a compound called B663, which proved to be extraordinarily effective against leprosy — a disease that still devastated communities in many parts of the world.

That compound would later become known as clofazimine, and was adopted in the early 1960s as an essential part of leprosy treatment, officially incorporated into the World Health Organization’s recommendations in 1981 — and still in use today.

Thanks to that discovery, hundreds of thousands of people were cured or freed from social isolation — a remarkable achievement that, interestingly enough, was born in a modest Irish laboratory, far from the world’s great research centres.

Ernest Walton (1903–1995), born in Waterford, was not just another physicist — he was a pioneer of nuclear physics. In 1932, alongside John Cockcroft, he succeeded in splitting the nucleus of a lithium atom by bombarding it with high-speed particles — something that had never been done before. To achieve this, they built the Cockcroft–Walton generator, a type of linear particle accelerator that propelled particles to collide with the atom, releasing energy and opening up an entirely new world.

The achievement seemed almost magical: suddenly, atoms, once invisible and impenetrable, could be manipulated, studied, and understood. In 1951, Walton and Cockcroft received the Nobel Prize in Physics — a well-deserved recognition for an experiment that changed the course of science, paving the way for nuclear physics. But Walton’s true impact went beyond awards or laboratories: he left a lasting mark on science, inspiring new generations and proving that even in a small country, one could uncover the deepest secrets of matter.

The list is endless, and the more I dig, the more genius I uncover… At times it even feels as though I’ve reached the centre of the Earth. But the inventions keep coming, and I wouldn’t be surprised if, with so much digging, I ended up piercing the surface… Better stop here, before we all get disintegrated into space.

Comentários