Pearse: muito além do seu tempo/Pearse: Far Ahead of His Time

- luaemp

- há 3 horas

- 9 min de leitura

Visitei o museu dedicado a Pádraig Pearse e saí de lá profundamente ensimesmada.

Há figuras que não pertencem totalmente ao seu tempo. Caminham à frente — muito à frente — incompreendidas, movidas por uma ideia maior do que elas próprias.

Pearse foi uma delas. Poderia ter ficado na História como um rebelde — mais um. Já seria suficiente, porque assim o é quem coloca a sua vida a servir a liberdade.

Mas ele foi mais longe… Sublinhando que liberdade não é apenas conquista política, mas também um pacto com a memória, a poesia e a identidade de um povo.

Faz sentido a pergunta escrita numa das primeiras salas do museu: Who do you think Pearse is?

Permitam-me que o vos apresente…

Nascido em Dublin, em 1879, Pádraig Pearse foi poeta, educador, sonhador e revolucionário — alguém que acreditava que a identidade de um povo começa na língua, na cultura e na imaginação. Desde cedo percebeu que uma nação se ergue primeiro no coração e na mente dos seus jovens, antes mesmo de se afirmar politicamente.

Cresceu entre livros, poesia e as histórias da Irlanda antiga. Nesse convívio íntimo com a memória do seu povo, compreendeu que a língua, a cultura e a tradição eram tão essenciais quanto a própria liberdade. Foi essa convicção que o levou a dedicar a vida a despertar a identidade irlandesa através da educação e da arte.

Formou-se em Direito, mas nunca exerceu como advogado. O seu verdadeiro compromisso não era com tribunais, mas com ideias, palavras e futuros possíveis.

Em Rathfarnham, fundou a St. Enda’s School (Scoil Éanna), um internato (“scoil chónaithe”, em irlandês) para rapazes, e logo depois uma escola para raparigas — Scoil Íde — porque entendia que o renascimento da Irlanda não poderia excluir metade do seu povo.

Entre salas de aula, livros, manuscritos e jardins, ensinava que a liberdade começa com o conhecimento, a poesia e a memória de quem somos.

Em ambas, a aprendizagem não se limitava a regras e fórmulas; era música, arte, história, poesia — era o cultivo da alma irlandesa.

Talvez esse conceito diferenciador tenha sido inspirado pelo ideal da educação da Grécia Clássica, que cultivava mente, corpo e espírito.

Mas o que se sabe, até porque escreveu vários textos sobre o tema, é que Pearse se deslocou à Bélgica em 1905, onde visitou escolas bilingues progressivas — experiência que enriqueceu a sua visão educativa e a sua forma de estruturar a escola, sempre atenta ao desenvolvimento integral dos alunos.

O próprio exemplo artístico da família foi determinante: o pai, James, dirigia uma oficina de escultura em Dublin, e o irmão, William, também escultor, deixou obras que hoje podem ser admiradas no museu.

Essa vivência com a arte preparou o caminho para que, na escola, escultura, música e peças em irlandês — como An Rí (O Rei), escritas e encenadas por Pearse no próprio jardim — traçassem um mapa onde arte, expressão e identidade cultural se entrelaçavam com o ensino. Essa experiência formava não apenas mentes e corações, mas também um senso de pertença e liberdade que ultrapassava as salas de aula, inspirando duradouramente gerações posteriores de irlandeses.

Mas Pearse não se contentava apenas com palavras. Militante da IRB — a Irish Republican Brotherhood, uma sociedade secreta que lutava pela independência da Irlanda — acreditava que a liberdade só se concretizava através da acção.

Em 1916, no Levante da Páscoa, ele e outros sonhadores, unidos por esse compromisso, proclamaram a República e ergueram a bandeira da Irlanda sobre Dublin. Embora o levante tenha falhado militarmente, nasceu aí um símbolo eterno de coragem, idealismo e luta pela independência.

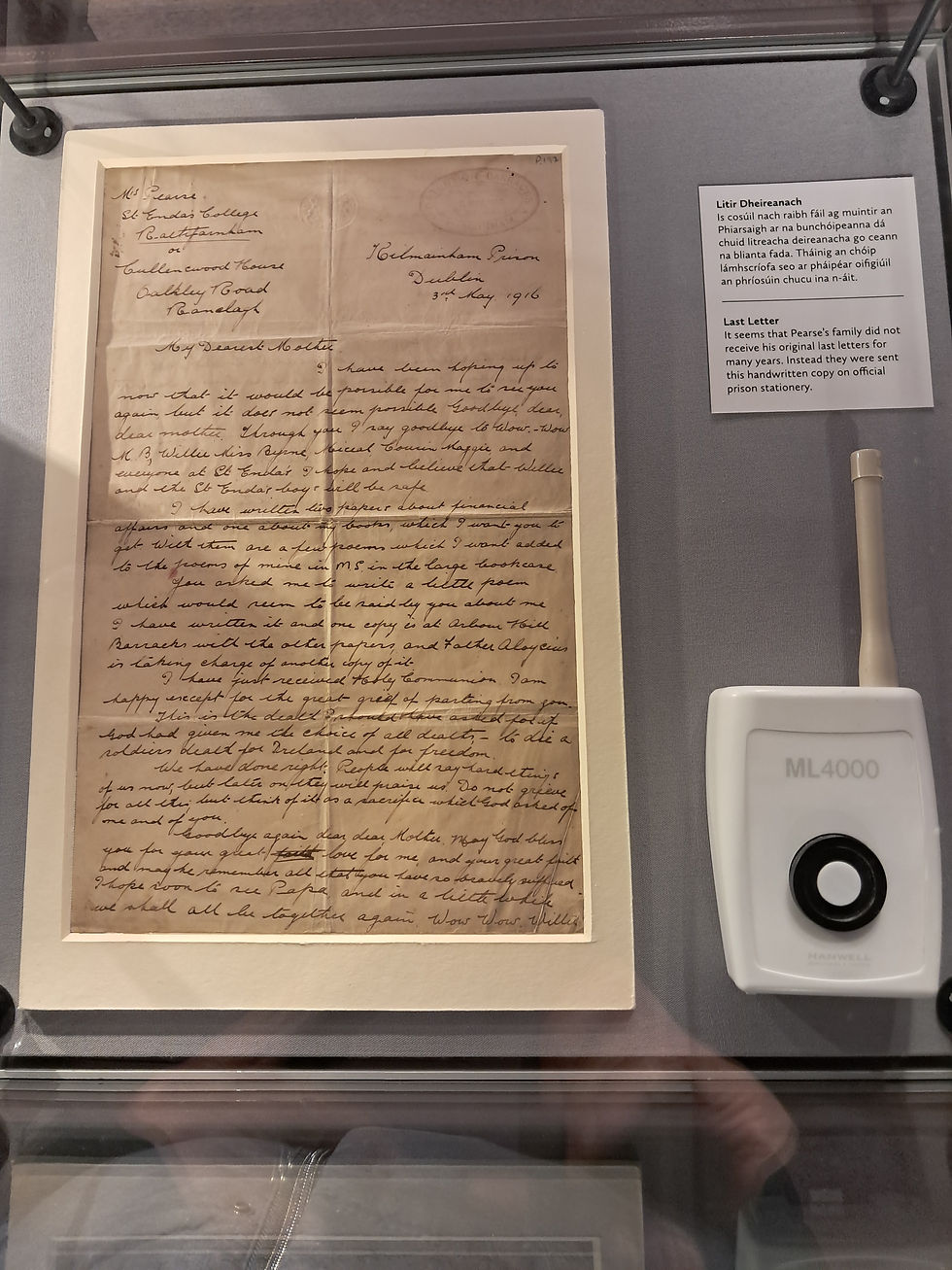

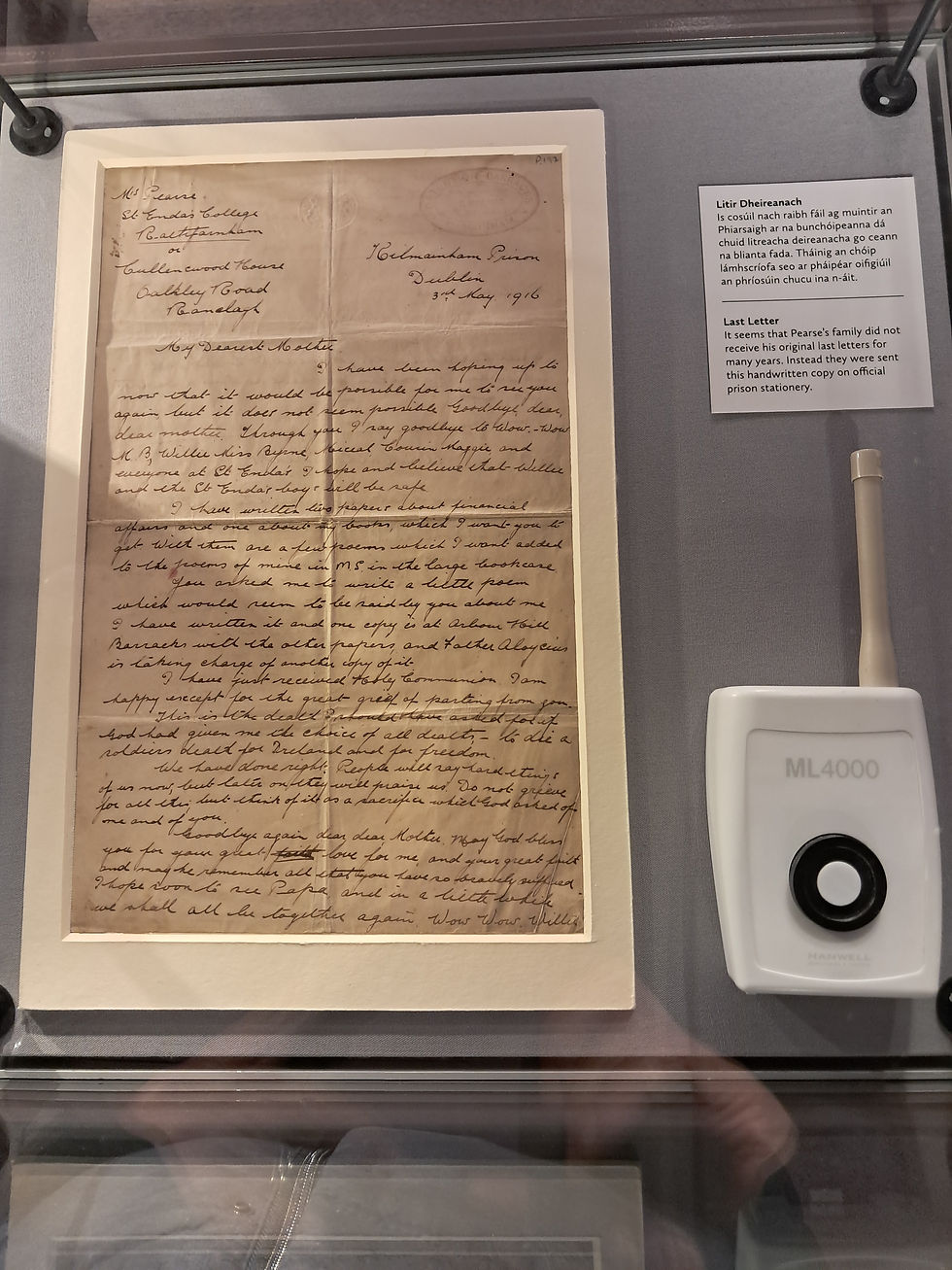

Preso, Pearse enfrentou o destino com a mesma coragem que ensinava aos seus alunos. Aos 36 anos, foi executado — ou, como disse a anfitriã do museu, “assassinado” — termo que, também para mim, expressa melhor a verdade.

A última sala do museu é devastadora porque nela se percebe que o sacrifício de Pádraig não foi solitário. Ao seu lado, Willie, o irmão mais novo, partilhou sonhos, coragem e, no fim, o mesmo destino trágico. Aquele espaço não guarda apenas objetos, mas ecos de vidas entrelaçadas pelo ideal e pela perda.

O pai, James Pearse, viu desmoronar o mundo que construiu para os filhos. Entre ferramentas e obras, carregou a dor silenciosa de um homem que ensinou a criar formas e palavras, mas que nada pôde fazer para evitar o desfecho trágico dos filhos.

A mãe, Margaret Brady, viveu para ver os filhos mortos pela causa que tanto amavam. Depois da execução de ambos, tornou‑se uma figura pública, envolvendo‑se explicitamente na política — foi eleita para o Parlamento (o Dáil) em 1921 como membro do Sinn Féin e participou como fundadora do Fianna Fáil, embora não tenha voltado a ser eleita para o Parlamento pelo partido.

Possivelmente, esta decisão foi uma tentativa de ajudar a preservar na memória colectiva a indecência de um desfecho injusto que lhe levou os filhos, carregando consigo um luto silencioso, profundo e impossível de medir.

As irmãs de Pádraig também viveram a tragédia de formas diferentes. Margaret, a filha mais velha, transformou a dor em acção concreta: organizou e preservou cartas, documentos e objectos pessoais dos irmãos, escreveu memórias e relatos sobre a vida deles e tornou-se uma voz activa na política e na cultura irlandesa, servindo como TD de 1933 a 1937 e depois como Senadora até 1968, garantindo que o legado deles permanecesse vivo na história e na consciência do povo.

Mary Brigid, a mais jovem, sentiu o horror de ver os irmãos arriscarem tudo e perderem a vida; amava profundamente Pádraig e Willie e, embora compartilhasse o ideal de independência, não concordava com a acção armada que eles escolheram. Viveu o luto com uma mistura de admiração, medo e saudade silenciosa, dedicando-se ao que sempre havia feito como professora de música e compositora, e preservando a memória do irmão através da publicação de The Home Life of Pádraig Pearse.

No fim da visita, a pergunta voltava a impor-se: Who do you think Pearse is?

Não é fácil responder. Pearse não cabe num rótulo confortável. Não foi apenas um revolucionário, nem apenas um poeta, nem apenas um educador. Foi alguém que acreditou — talvez com demasiada lucidez para o seu tempo — que a liberdade sem cultura é frágil e que uma nação sem memória está condenada a viver o silêncio.

Ao sair do museu, não trazia respostas.

Trazia admiração e inquietação.

Creio que é isso que distingue as figuras que realmente importam: obrigam-nos a questionar, a reflectir, a colocar tudo em perspectiva, reposicionando-nos perante a pertença da memória — e todo o resto — e ao cuidado com que escolhemos habitá-la.

English version

I visited the museum dedicated to Pádraig Pearse and left it deeply introspective.

There are figures who do not fully belong to their time. They walk ahead — far ahead — misunderstood, driven by an idea greater than themselves.

Pearse was one of them. He could have gone down in History as a rebel — just another one. That alone would have been enough, for so it is with anyone who places their life in the service of freedom.

But he went further… Emphasising that freedom is not merely a political conquest, but also a pact with memory, poetry, and the identity of a people.

The question written in one of the museum’s first rooms makes sense: Who do you think Pearse is?

Allow me to introduce him to you…

Born in Dublin in 1879, Pádraig Pearse was a poet, educator, dreamer, and revolutionary — someone who believed that a people’s identity begins with language, culture, and imagination. From an early age, he understood that a nation rises first in the hearts and minds of its young, even before it asserts itself politically.

He grew up surrounded by books, poetry, and the stories of ancient Ireland. Through this intimate closeness with his people’s memory, he came to understand that language, culture, and tradition were as essential as freedom itself. It was this conviction that led him to devote his life to awakening Irish identity through education and art.

He earned a BA in Law, but never practised as a lawyer. His true commitment was not to courts, but to ideas, words, and possible futures.

In Rathfarnham, he founded St. Enda’s School (Scoil Éanna), a boarding school (scoil chónaithe, in Irish) for boys, and shortly thereafter a school for girls — Scoil Íde — because he believed that Ireland’s rebirth could not exclude half of its people.

Between classrooms, books, manuscripts, and gardens, he taught that freedom begins with knowledge, poetry, and the memory of who we are.

In both schools, learning was not limited to rules and formulas; it was music, art, history, poetry — it was the cultivation of the Irish soul.

Perhaps this distinctive concept was inspired by the ideal of Classical Greek education, which cultivated mind, body, and spirit.

But what is known, not least because he wrote several texts on the subject, is that Pearse traveled to Belgium in 1905, where he visited progressive bilingual schools — an experience that enriched his educational vision and the way he structured the school, always attentive to the students’ holistic development.

The family’s own artistic example was also decisive: his father, James, ran a sculpture workshop in Dublin, and his brother, William, also a sculptor, left works that can still be admired in the museum today.

This immersion in art paved the way for sculpture, music, and plays in Irish — such as An Rí (The King), written and staged by Pearse in the school garden — to map out a space where art, expression, and cultural identity intertwined with teaching. This experience shaped not only minds and hearts but also a sense of belonging and freedom that extended beyond the classrooms, inspiring generations of Irish people for years to come..

But Pearse was not content with words alone. A member of the IRB — the Irish Republican Brotherhood, a secret society that fought for Ireland’s independence — he believed that freedom could only be realized through action.

In 1916, during the Easter Rising, he and other dreamers, united by this commitment, proclaimed the Republic and raised the Irish flag over Dublin. Although the rising failed militarily, it gave birth to an enduring symbol of courage, idealism, and the struggle for independence.

Imprisoned, Pearse faced his fate with the same courage he taught his students. At the age of 36, he was executed — or, as the museum host put it, “murdered” — a term that, to me as well, better conveys the truth.

Their father, James Pearse, saw the world he had built for his children collapse. Amid tools and artworks, he carried the silent grief of a man who had taught others to shape forms and words, yet could do nothing to prevent his children’s tragic fate.

Their mother, Margaret Brady, lived to see her children killed for the cause they loved so dearly. After their executions, she became a public figure, engaging actively in politics — elected to Parliament (the Dáil) in 1921 as a member of Sinn Féin and later participating as a founder of Fianna Fáil, although she was never elected to Parliament again under the party.

Possibly, this decision was an attempt to help preserve in the collective memory the injustice of an outcome that took her children, carrying with her a silent, profound, and immeasurable grief.

Pádraig’s sisters also experienced the tragedy in different ways. Margaret, the eldest, transformed her pain into concrete action: she organized and preserved letters, documents, and personal belongings of her brothers, wrote memoirs and accounts of their lives, and became an active voice in Irish politics and culture, serving as a TD from 1933 to 1937 and then as a Senator until 1968, ensuring that their legacy remained alive in the history and consciousness of the people.

Mary Brigid, the youngest, felt the horror of seeing her brothers risk everything and lose their lives; she loved Pádraig and Willie deeply, and although she shared their ideal of independence, she did not agree with the armed action they chose. She lived her grief with a mixture of admiration, fear, and silent longing, dedicating herself to what she had always done as a music teacher and composer, and preserving her brother’s memory through the publication of The Home Life of Pádraig Pearse.

At the end of the visit, the question arose again: Who do you think Pearse is?

It is not an easy question to answer. Pearse does not fit into a comfortable label. He was not just a revolutionary, nor just a poet, nor just an educator. He was someone who believed — perhaps with too much clarity for his time — that freedom without culture is fragile, and that a nation without memory is condemned to live in silence.

Leaving the museum, I carried no answers.

I carried admiration and unease.

I believe this is what distinguishes the figures who truly matter: they compel us to question, to reflect, to put everything into perspective, repositioning ourselves before the belonging of memory — and everything else — and the care with which we choose to inhabit it.

Comentários