Primeiros passos em Wexford: Ferns/First Steps in Wexford: Ferns

- luaemp

- 28 de set. de 2025

- 12 min de leitura

(Followed by the English version)

“Queres ir a County Wexford?”

Mas é que nem se pergunta!

E lá fui, fazer o ritual de iniciação a um novo condado…

O condado de Wexford fica no extremo sudeste da Irlanda, na província de Leinster, conhecida pelo slogan turístico “The Sunny South-East” — porque, de facto, tem mais horas de sol do que a média do resto da Irlanda. Fica situado na costa, com longas praias de areia, portos históricos e uma paisagem marcada por colinas suaves, campos agrícolas e a Península de Hook, onde se ergue um dos faróis mais antigos do mundo ainda em funcionamento.

E já com aquela ânsia, desnorteada, tal e qual o Coelho da Alice, mal pude esperar pela boleia…

Primeiro destino: Ferns.

A vila, pequena e tranquila como tantas outras, carrega uma história que se estende por séculos. Pensar que Ferns foi, no século XII, a capital do reino de Uí Cheinnselaig e um importante centro eclesiástico, dá vontade de parar e ouvir as histórias que exalam das suas ruínas.

O carro desfez a curva e logo mostrou St. Mary's Abbey, uma ruína medieval que marca o início da Ferns Heritage Trail. Esta abadia agostiniana foi fundada por Diarmait Mac Murchada entre 1158 e 1162, sobre um local de fundação cristã anterior. Dela apenas restam vestígios significativos da sua arquitectura medieval, incluindo uma torre única que combina base quadrada com estrutura cilíndrica.

Nas suas proximidades encontra-se o Poço de S. Mogue (St. Mogue’s Well), local de peregrinação associado a S. Aidan, o primeiro bispo da diocese de Ferns. Este conjunto de ruínas medievais oferece uma visão fascinante da história religiosa e arquitectónica da região.

A necessidade de cafeína, desta vez não minha — embora nunca diga não a um café —, levou-nos a um Pub, com vistas para o castelo — eu diria, basicamente em cima deste…

De referir que o Pub é giro, o café bom, e a esplanada confortável…

Mais recompostas, lá fomos à visita…

A história é longa mas vou tentar abreviar…

O castelo — janela viva sobre o passado normando da região — foi erguido por volta de 1220 por William Marshal, conde de Pembroke, num lugar que já tinha sido residência dos reis de Leinster. Hoje resta apenas parte da estrutura original, mas mesmo assim é imponente. A torre sudeste guarda ainda uma capela circular normanda, com tecto abobadado, lareiras originais e uma câmara subterrânea que nos transporta para um quotidiano distante.

Durante escavações feitas nos anos 1970, descobriu-se o fosso embutido na rocha que rodeava a fortificação e vestígios de uma ponte levadiça — sinais claros da sua função defensiva. O castelo, ao longo dos séculos, foi passando de mãos em mãos, dos Kavanaghs MacMurroughs às autoridades inglesas, até que no século XVII sofreu graves danos, sobretudo durante a campanha de Cromwell em 1649.

Mesmo reduzido ao que resta, é fácil imaginar a imponência do quadrado original, com as quatro torres a marcarem a paisagem. Lá de cima, o olhar alcança a vila e os campos verdejantes ao redor, o mesmo horizonte que já terá sido vigiado por guerreiros e senhores de terras. No centro de visitantes, podemos ver o Ferns Tapestry, um bordado de 15 metros, executado por membros da comunidade local, composto por 25 painéis em lã crewel que contam a história da vila desde a chegada de S. Aidan no século VI até à invasão normanda.

O castelo não é apenas uma ruína; é um símbolo da importância estratégica e política da vila ao longo da Idade Média e visitar os seus restos permite imaginar os tempos em que aqui se decidiam destinos e se travavam batalhas.

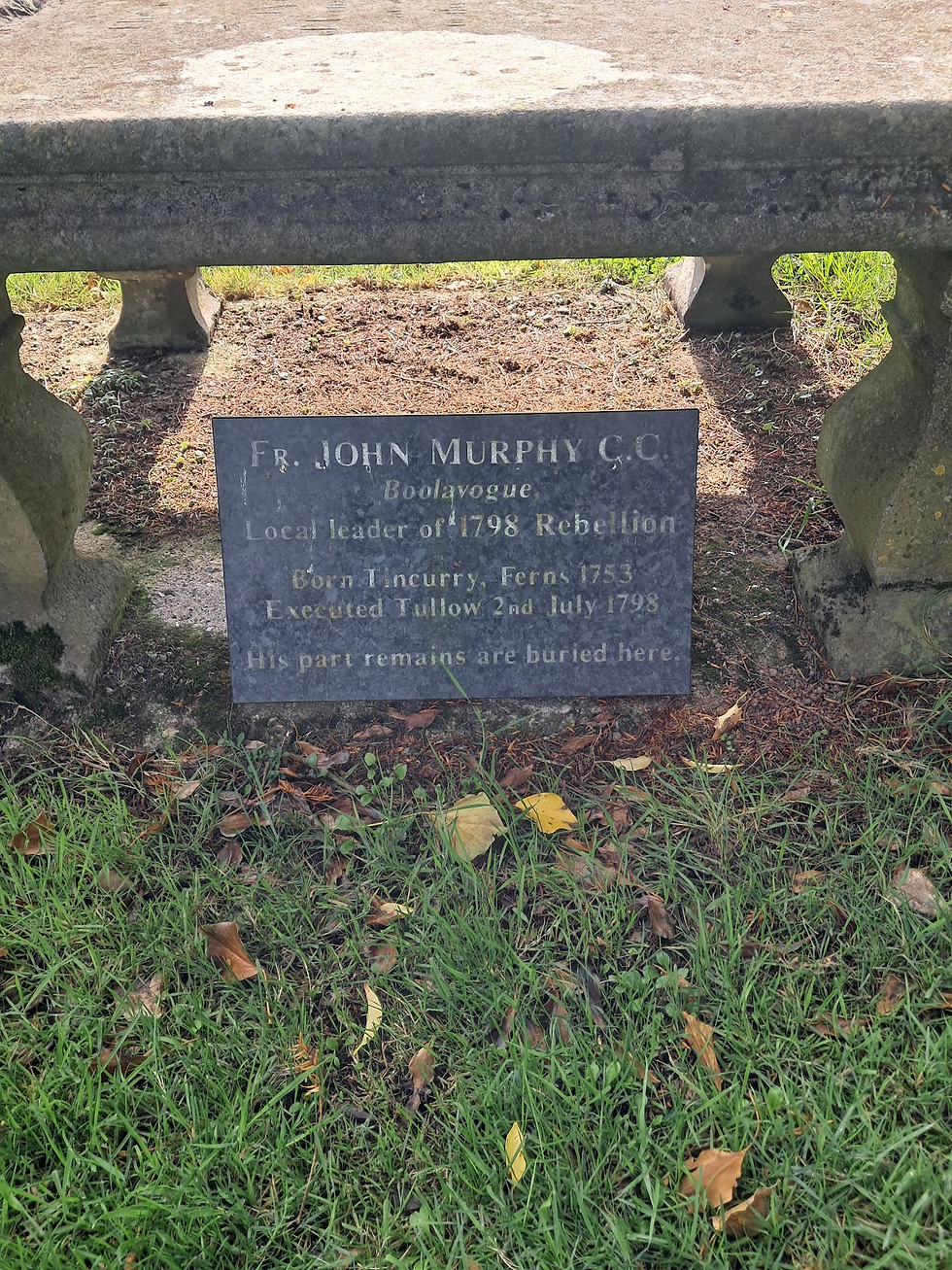

À saída, o olhar pousa num monumento em jeito de memorial: uma cruz celta, altiva e serena, ocupa o centro da praça. Desenhada pelo escultor John Walsh e construída em 1953, homenageia o Padre John Murphy, que não se limitou a guiar a paróquia, mas assumiu o comando dos insurgentes na Rebelião de 1798, tornando-se símbolo de coragem e resistência.

Natural de Tincurry, perto de Ferns, Murphy conduziu os revoltosos em confrontos decisivos, como a batalha de Oulart Hill, até ser capturado e executado em Tullow. A sua memória permanece viva, gravada tanto na pedra quanto na história da região.

Daqui dá para ver a igreja de St. Aidan (ou Edan), cuja primeira pedra foi colocada no dia 31 de Janeiro de 1974 — dia do santo — e acabada de construir em Fevereiro do ano seguinte.

Há, porém, não muito distante dali, uma Catedral com o mesmo nome. O que me fez pensar “com os meus botões”: Hum, quem foi esta figura para ter direito a duas igrejas locais com o seu nome?”

Pois bem, foi o primeiro bispo cristão da região de Ferns, no século VI, e fundador da diocese local. A sua chegada ditou o início da organização cristã na área, que até então era marcada por pequenos centros monásticos e comunidades dispersas. A sua missão consistiu em evangelizar, organizar comunidades religiosas e consolidar a presença do cristianismo num território ainda fortemente influenciado pelas tradições pagãs celtas.

A sua influência foi tão grande que Ferns tornou-se num importante centro eclesiástico durante séculos. A cidade acolheu a construção da catedral medieval e de diversas igrejas paroquiais, mantendo sempre o legado de St. Aidan como guia espiritual.

Ora a actual catedral íntegra partes da igreja anterior construída no século XIII e parcialmente destruída por um incêndio no século XVI. No seu interior encontra-se a efígie tumular de 800 anos do bispo John, St John (falecido em 1243), representado com mitra e báculo tendo os pés apoiados num cão — um exemplo raro da escultura funerária medieval irlandesa. Outros elementos medievais que sobreviveram ao incêndio foram a dupla pia (espécie de lavatório em pedra, usadas para lavar vasos sagrados e as mãos do celebrante) e colunas com marcas de pedreiro que permanecem visíveis, oferecem uma ligação directa ao passado e à prática litúrgica antiga.

O respectivo cemitério também exala história — e polémica. Dizem, alguns, que o rei Diarmait MacMurrough, aquele que trouxe os normandos para a Irlanda no século XII, ali, meio perdido no espaço, descansa num túmulo pouco representativo da grandeza do seu papel na história, assinalado apenas pelo que resta de uma antiga high cross (cruz celta alta). Outros sustentam que, como rei e fundador da St. Mary’s Abbey, teria sido sepultado nessa abadia — cujas ruínas estão mesmo ao lado. Logo, o que se vê hoje no cemitério da catedral talvez não seja o túmulo em si, mas antes um memorial sobrevivente, um vestígio arrancado às destruições do tempo e que a tradição popular acabou por ligar ao rei.

Também o túmulo do Padre John Murphy pode ser encontrado neste cemitério.

Podemos igualmente apreciar o expressivo trabalho do entalhador James Byrne, artesão de lápides activo em Ferns durante os finais do século XVIII e início do XIX, cujas assinaturas são visíveis em várias lápides ornamentadas no cemitério da Catedral. As suas obras destacam-se por cenas de crucificação — com Jesus na cruz, Maria e João —, por símbolos como o Christograma IHS envolto em raios solares, e por detalhes como a lua e o sol, halos, figuras humanas vestidas à moda da época, tudo gravado em pedra da região.

Seguindo caminho, mais uma homenagem a S. Aidan, desta vez feita pelas Irmãs da Adoração, que ergueram em 1990, no local da antiga igreja católica, um convento e uma igreja de adoração perpétua. Um lugar simples, construído quase todo com materiais locais, que devolve à paisagem o espírito de recolhimento iniciado há mais de mil anos, sem abdicar do conforto actual.

Mas há mais… Nunca vi tanta igreja junta numa vila tão pequena! Nem tantas incertezas arqueológicas…

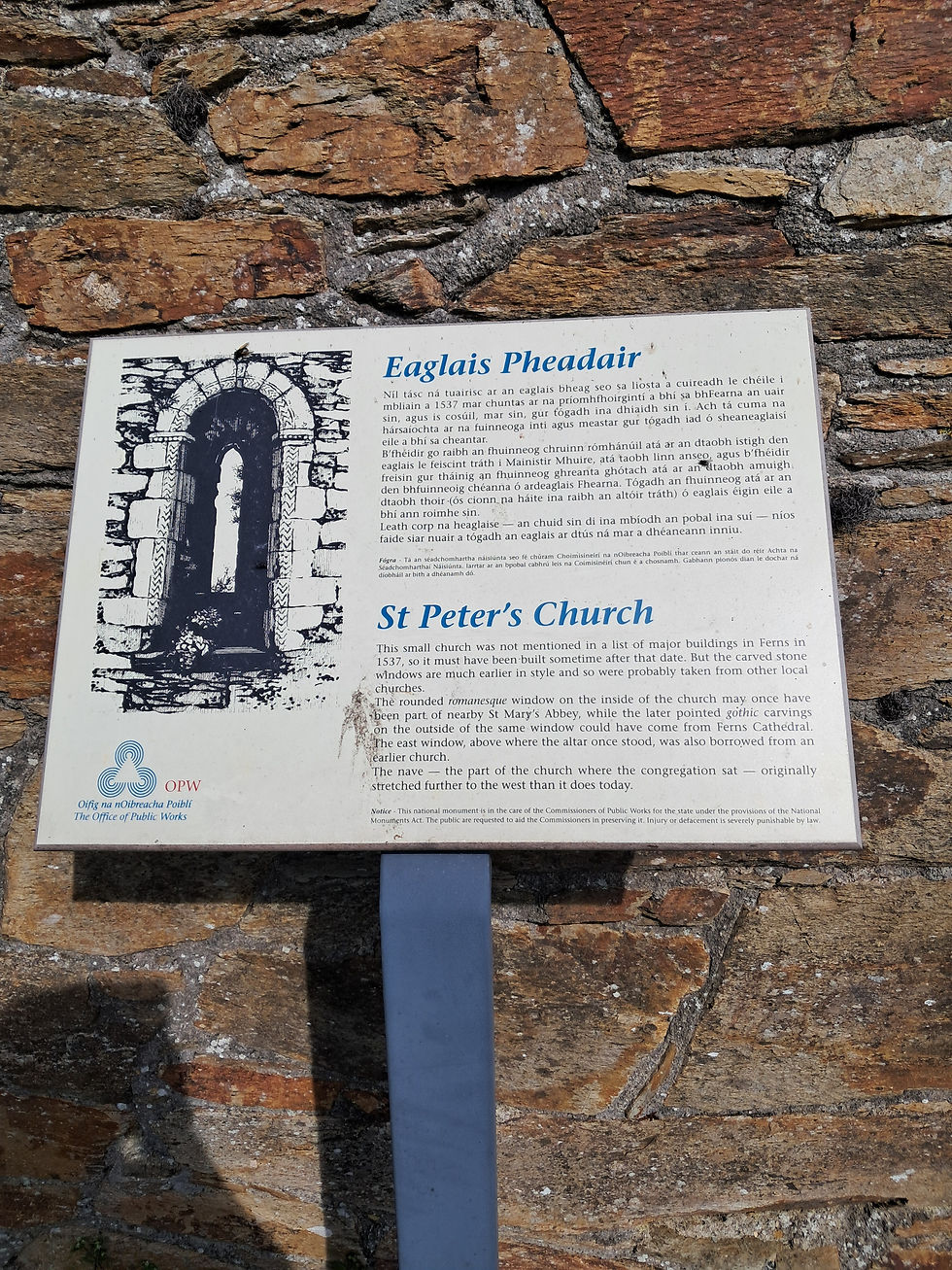

A de St. Peter, está em ruínas e o que dela sobra levanta muitas dúvidas quanto à sua datação. Dizem os historiadores que ela não consta da lista de 1537 dos principais edifícios de Ferns. Logo presume-se que seja posterior a essa data. Porém há elementos na sua construção que parecem contradizer, ou pelo menos baralhar, esta presunção. As pedras que constituem a janela sul ou as duas janelas lancetadas do que resta da parede oeste, são anteriores ao século XVI. Uma das explicações é a de que poderão ter sido retiradas de igrejas que, à época, já estivessem em ruínas como a vizinha igreja de St. Mary's Abbey ou a Igreja de Clone.

Que é bonita, é. Deixemos o mistério para quem de direito resolver.

Não posso resistir a dizer-vos que ao longo do percurso histórico — HeritageTrail de Ferns— , foram estrategicamente colocadas réplicas (cinco ao todo) de capacetes normandos que, quando levantados, nos revelam uma pequena escultura da autoria de Tomas McCullum, acompanhadas de um painel gráfico que apresenta um fragmento da história local.

Uma ideia muito bem engendrada, já que os capacetes evocam precisamente a herança militar e medieval: representam os guerreiros normandos que marcaram a história da vila e que mudaram para sempre o rumo da Irlanda. Poeticamente, interpretei este gesto de levantar o capacete não como a curiosidade de quem quer imaginar como seria o rosto de um soldado, mas como o abrir de uma janela para o passado, transformando um objecto de guerra num convite à memória e à descoberta.

Um tanto cansada mas feliz por tanta descoberta, dei por mim a pensar que, se este foi apenas o primeiro destino, o que mais guardará o Condado de Wexford na manga? A aventura estava só a começar.

English Version

"Do you want to go to County Wexford?"

But that's not even a question!

And off I went, performing the initiation ritual for a new county…

County Wexford lies in the far southeast of Ireland, in the province of Leinster, known by the tourist slogan “The Sunny South-East” — because, in fact, it enjoys more hours of sunshine than the Irish average. It sits on the coast, with long sandy beaches, historic ports, and a landscape marked by gentle hills, farmland, and the Hook Peninsula, home to one of the oldest operational lighthouses in the world.

And already with that restless, dizzying excitement, just like Alice’s White

Rabbit, I could hardly wait for the ride…

First destination: Ferns.

The village, small and serene like so many others, carries a history that stretches across centuries. To think that Ferns was, in the 12th century, the capital of the kingdom of Uí Cheinnselaig and an important ecclesiastical centre makes one want to pause and listen to the stories that still emanate from its ruins.

The car rounded the bend and immediately revealed St. Mary’s Abbey, a medieval ruin that marks the beginning of the Ferns Heritage Trail. This Augustinian abbey was founded by Diarmait Mac Murchada between 1158 and 1162, on a site of earlier Christian foundation. All that remains are significant traces of its medieval architecture, including a unique tower that combines a square base with a cylindrical structure.

Nearby lies St. Mogue’s Well, a place of pilgrimage associated with St. Aidan, the first bishop of the diocese of Ferns. This cluster of medieval ruins offers a fascinating glimpse into the religious and architectural history of the region.

The need for caffeine — not mine this time, though I never say no to a coffee — led us to a pub overlooking the castle, or rather, practically on top of it…

It’s worth mentioning that the pub is charming, the coffee good, and the terrace comfortable…

Feeling a little more restored, off we went for the visit…

The story is a long one, but I’ll try to keep it brief…

The castle — a living window onto the Norman past of the region — was built around 1220 by William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, on a site that had already been the residence of the kings of Leinster. Today, only part of the original structure remains, yet it is still imposing. The southeast tower still holds a circular Norman chapel, with a vaulted ceiling, original fireplaces, and an underground chamber that carries us back into a distant daily life.

Excavations carried out in the 1970s uncovered the rock-cut moat that once surrounded the fortress, along with traces of a drawbridge — clear signs of its defensive purpose. Over the centuries, the castle passed from hand to hand, from the Kavanaghs MacMurroughs to the English authorities, until in the 17th century it suffered severe damage, especially during Cromwell’s campaign in 1649.

Even reduced to what remains, it’s easy to imagine the imposing square of the original structure, with its four towers marking the landscape. From the top, the gaze reaches the village and the green fields beyond — the same horizon that was once watched over by warriors and lords of the land. In the visitor centre, one can see the Ferns Tapestry, a 15-metre-long embroidery created by members of the local community, composed of 25 crewel-wool panels that tell the story of the village from St. Aidan’s arrival in the 6th century to the Norman invasion.

The castle is not merely a ruin; it is a symbol of the village’s strategic and political importance throughout the Middle Ages, and visiting its remains allows one to imagine the times when destinies were decided and battles fought here.

On leaving, the eye rests on a monument that serves as a memorial: a Celtic cross, proud and serene, occupies the centre of the square. Designed by the sculptor John Walsh and erected in 1953, it honours Father John Murphy, who not only guided the parish but took command of the insurgents in the 1798 Rebellion, becoming a symbol of courage and resistance.

Born in Tincurry, near Ferns, Murphy led the rebels in decisive confrontations such as the Battle of Oulart Hill, until he was captured and executed in Tullow. His memory remains alive, etched both in stone and in the history of the region.

From here, one can see St. Aidan’s (or Edan’s) Church, whose foundation stone was laid on 31 January 1974 — the saint’s day — and was completed the following February.

Not far from there, however, stands a cathedral bearing the same name. This made me think to myself: “Hmm, who was this figure to deserve two local churches named after him?”

Well, he was the first Christian bishop of the Ferns region, in the 6th century, and the founder of the local diocese. His arrival marked the beginning of organized Christianity in the area, which until then had been characterised by small monastic centres and scattered communities. His mission was to evangelize, organize religious communities, and consolidate the presence of Christianity in a territory still strongly influenced by Celtic pagan traditions.

His influence was so great that Ferns became an important ecclesiastical centre for centuries. The town hosted the construction of the medieval cathedral and several parish churches, always maintaining St. Aidan’s legacy as a spiritual guide.

The current cathedral incorporates parts of the earlier church built in the 13th century, which was partially destroyed by fire in the 16th century. Inside, one can find the 800-year-old effigy of Bishop John, St. John (died 1243), depicted with a mitre and crozier, his feet resting on a dog — a rare example of medieval Irish funerary sculpture. Other medieval elements that survived the fire, such as the double piscina (stone basins used for washing sacred vessels and the celebrant’s hands) and columns bearing visible mason’s marks, offer a direct link to the past and to ancient liturgical practice.

The adjoining cemetery also exudes history — and controversy. Some say that King Diarmait MacMurrough, the one who brought the Normans to Ireland in the 12th century, lies there, somewhat lost in space, in a tomb that hardly reflects the magnitude of his role in history, marked only by what remains of an ancient high cross. Others argue that, as king and founder of St. Mary’s Abbey, he would have been buried in that abbey — whose ruins lie just beside it. Therefore, what is seen today in the cathedral cemetery may not be the tomb itself, but rather a surviving memorial, a vestige wrested from the destructions of time and that popular tradition has come to associate with the king.

The tomb of Father John Murphy can also be found in this cemetery.

One can also admire the striking work of the carver James Byrne, a tombstone artisan active in Ferns during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, whose signatures are visible on several ornate gravestones in the cathedral cemetery. His works stand out for scenes of the Crucifixion — with Jesus on the cross, Mary, and John — for symbols such as the IHS Christogram surrounded by sunrays, and for details like the moon and the sun, halos, and human figures dressed in the fashion of the time, all carved from local stone.

Continuing on, another tribute to St. Aidan awaits, this time by the Sisters of Adoration, who in 1990 built, on the site of the old Catholic church, a convent and a church for perpetual adoration. A simple place, constructed almost entirely from local materials, it restores to the landscape the spirit of devotion begun over a thousand years ago, without sacrificing modern comfort.

But there’s more… I’ve never seen so many churches together in such a small village! Nor so many archaeological uncertainties…

St. Peter’s is in ruins, and what remains raises many questions regarding its dating. Historians say it does not appear in the 1537 list of Ferns’ main buildings, so it is assumed to be later than that. However, elements in its construction seem to contradict, or at least confuse, this assumption. The stones forming the south window, or the two lancet windows of what remains of the west wall, are from before the 16th century. One explanation is that they may have been taken from churches that were already in ruins at the time, such as the nearby St. Mary’s Abbey or Clone Church.

Is it beautiful? It certainly is. Let’s leave the mystery for those who have the right to solve it.

I can’t resist telling you that along the historical route — the Ferns Heritage Trail — five replicas of Norman helmets have been strategically placed. When lifted, they reveal a small sculpture by Tomas McCullum, accompanied by an information panel presenting a fragment of local history.

A very clever idea, since the helmets precisely evoke the military and medieval heritage: they represent the Norman warriors who shaped the village’s history and forever changed the course of Ireland. Poetically, I interpreted the act of lifting the helmet not as mere curiosity to imagine a soldier’s face, but as opening a window onto the past, transforming an object of war into an invitation to memory and discovery.

Somewhat tired but happy from so many discoveries, I found myself thinking that if this was only the first destination, what else might County Wexford have up its sleeve? The adventure was only just beginning.

Comentários