Skerries

- luaemp

- 3 de ago. de 2025

- 11 min de leitura

(Followed by the English version)

Lá voltei ao condado de Fingal…

Desta vez para visitar Skerries, uma vila costeira a 30 km de Dublin.

Primeiro houve uma curta paragem em Lusk, porque a necessidade de cafeína fala sempre mais alto. Lusk, parecia uma vila fantasma, deserta de vida, e com pouco para ver. Para fazerem uma ideia tive de perguntar onde poderia tomar um café, a duas almas que encontrei, pois não vislumbrava nenhum indício. Surpresas, talvez, pela pergunta, mandaram-me para o Lidl…

Disposta a seguir as instruções, basicamente já a ressacar, encontrei um pub e não fui mais longe…

Não vou tecer considerações sobre a qualidade do café, mas adorei o pub…

Aproveitando a paragem, não poderia deixar de investigar a torre que sobressaía na paisagem. Vai-se a ver… e era parte de um complexo eclesiástico. Ora, como costumo dizer, “por trás de uma bela torre há muito para aprender”, lá andei a ler sobre o assunto. A dita cuja, com 27 metros de altura, dá pelo nome de St. Macculin’s Round Tower e terá sido erguida por uma antiga comunidade monástica — como tantas outras torres redondas da Irlanda, pensadas para resistir ao tempo, aos vikings e às voltas da História. Ao lado, uma torre sineira quadrada do século XV e uma igreja do século XIX completam o trio, conferindo-lhe um ar peculiar. Três épocas diferentes a partilhar o mesmo adro, como se o passado não coubesse numa só época. E, claro, o cemitério, com as campas corroídas pelo tempo.

Não sei se por rivalidade, falta de imaginação ou pela importância do santo, há uma outra igreja na vila, desta feita católica, que dá pelo nome de St. MacCullin's Catholic Church. Projectada pelo arquiteto J. J. Robinson e construída entre 1924 e 1930, em estilo neo-românico, é uma das mais recentes da região. O edifício destaca-se pela sua arquitectura robusta, com paredes de granito trabalhado, janelas em arco e vitrais de Harry Clarke, um dos mestres do vitral irlandês. O interior possui uma nave abobadada e um altar com detalhes artísticos notáveis.

Não pude deixar de reparar nas bombas de água pontuando as ruas e a praça.

Deixei para trás Lusk, contente com as descobertas proporcionadas pela minha falta de cafeína…

Agora sim… Rumo a Skerries… Mas antes, Ardgillan Castle, que se ergue numa propriedade com cerca de 194 acres, em Balbriggan, a uns 6km de Skerries.

Construído em 1738 como “Prospect House” por Robert Taylor, acabou por ganhar mais alas no século XIX e um aspecto quase de castelo, mas sem perder o charme Vitoriano. Rodeado de jardins murados, entre eles o magnífico Jardim das Rosas —, trilhos, estábulos, estufas vitorianas, os courtyards (espaços de apoio rural, como era comum nestas propriedades), e vistas, soberbas para o mar e para as Montanhas de Mourne, já na Irlanda do Norte.

Hoje é um espaço público vibrante, com visitas guiadas, exposições, uma casa de chá instalada na antiga Cottage — Brambles Tea Room — e um parque infantil que, em 2018, foi distinguido com um prémio: o Pollinator Award que reconhece iniciativas ligadas à biodiversidade e à protecção de polinizadores.

Não tinha intenção de visitar o castelo por dentro. Mas mesmo que quisesse um letreiro na porta, desculpava-se por estarem momentaneamente canceladas, dada a gravação de um filme…

Próxima paragem: Skerries Mills. E que paragem! Um daqueles lugares que, à primeira vista, parece apenas pitoresco — com os seus moinhos bem compostos no horizonte — mas que, ao caminhar pelo espaço, vai revelando camadas de história, engenho e vida comunitária.

Este complexo único na Irlanda — e raro mesmo à escala europeia — reúne dois moinhos de vento, um moinho de água, uma antiga padaria e tudo o que um pequeno ecossistema rural exigia: canais, lagoas, hortas, trilhos e uma energia que, em tempos, alimentou toda uma vila. Literalmente.

O moinho de água original remonta ao século XIII e ainda funciona — alimentado por um sistema engenhoso de canais e comportas que fazem girar uma roda de madeira como nos velhos tempos. Um pouco mais acima, o moinho de colmo — mais modesto, com quatro pás — ergue-se sobre os restos de um antigo forte monástico. E, no alto da colina, o Great Windmill impõe-se com as suas cinco pás e uma presença quase teatral sobre a paisagem.

Há visitas guiadas que, pelo que dizem, explicam como tudo isto funcionava em conjunto — vento e água a moer farinha, operários a subir escadas estreitas, grãos a passar por tamises e rodas dentadas — até chegar à antiga padaria.

Hoje, essa padaria transformou-se no Watermill Café, com scones acabados de sair do forno, bolos, sopas e saladas servidas dentro ou no terraço com vista para os moinhos e para os campos de milho que ainda se cultivam ali à volta.

Uma loja de artesanato com peças de criadores locais, um pequeno museu com objectos históricos (incluindo relíquias do navio Tayleur, naufragado em 1854), e um parque infantil galardoado, em 2022, com o Pollinator Award, completam este complexo. Aos sábados, há ainda uma feira de produtores onde Skerries se reúne entre queijos, pães e conversas.

Skerries Mills é, mais do que um museu ao ar livre, um lugar vivo — onde se sente a ligação entre o passado e o presente, entre a terra e o mar, entre o engenho e a partilha. E mesmo que não se vá com intenção de moer nada, vimos de lá a moer — se não for uma refeição ou um scone com um chá, com certeza ideias, não faltarão para digerir…

Rumei para a marginal, para usufruir do resto da viagem. Não foi o céu carregado e as gotas de chuva que começaram a cair que me impediriam de levar a cabo o meu plano — até porque por cá ela em algum momento do dia está presente…

O porto, com os barcos a balançar preguiçosamente, parecia adormecido entre marés. O cais e seu farol na ponta… As gaivotas, indiferentes à chuva miudinha, fazendo os seus voos rasantes ou pousadas nos muros compunham o quadro juntamente com as casas coloridas, os cafés de portas abertas, o Clube de Vela de onde barcos entravam e saiam para o mar e o circuito à beira-mar que, como se não bastassem as vistas, é uma galeria a céu aberto com esculturas espalhadas ao longo do percurso e quadros informativos.

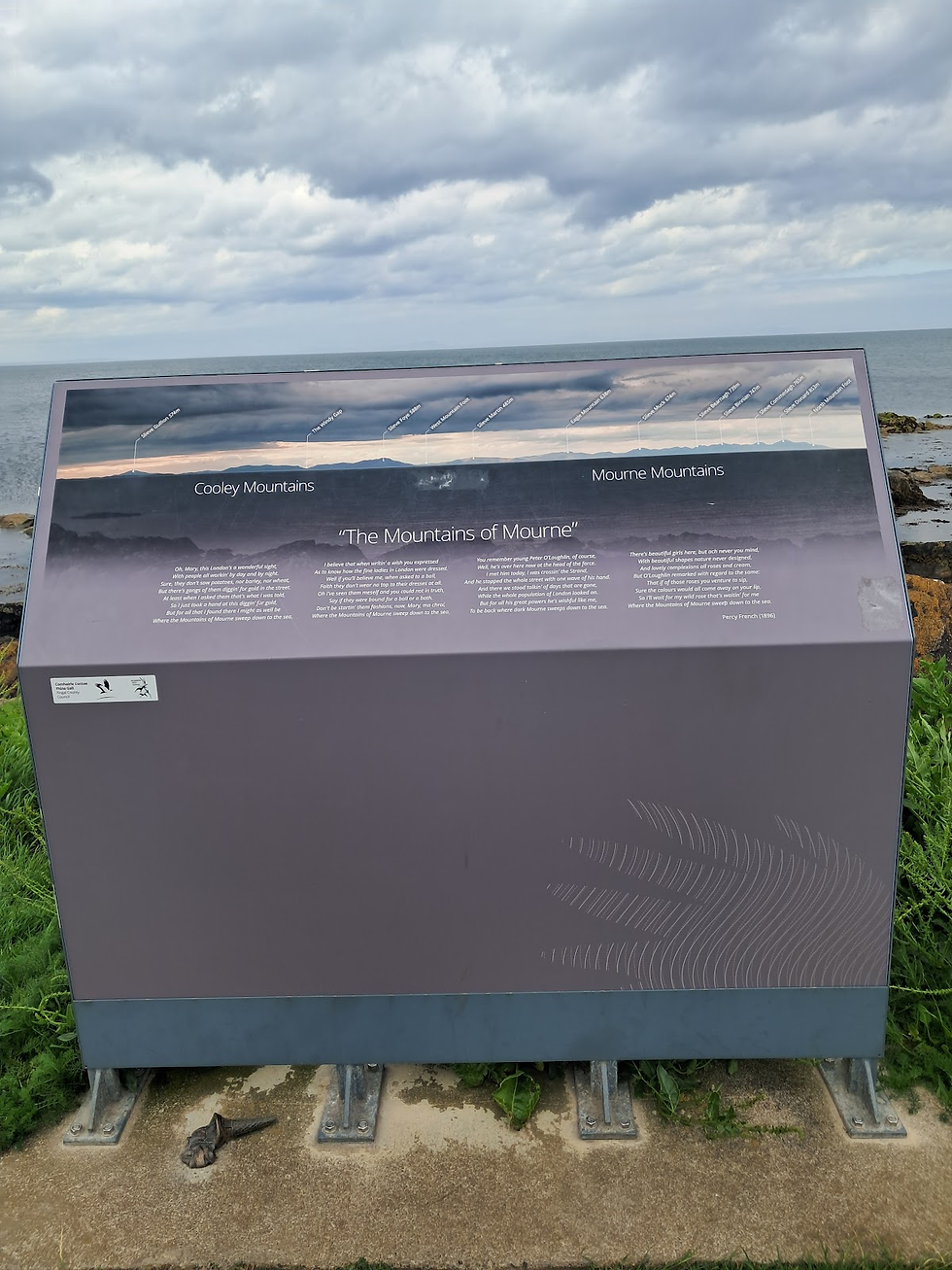

Entre elas, a Tidy Towns Sculpture, criada por Shane Holland, encomendada para celebrar o prémio National Tidy Towns de 2016, conquistado por Skerries; a escultura Terns, da artista irlandesa Bríd Ní Rinn; ou ainda um painel informativo sobre as Montanhas de Mourne, que dali se avistam em dias claros.

Na praça de Red Island, o Sea Pole Memorial — um antigo mastro de resgate transformado num monumento comovente, com os nomes de mais de 260 pessoas e navios perdidos no mar ao longo dos séculos. Inaugurado em 2013 pelo Presidente Michael D. Higgins, homenageia também a tripulação do helicóptero Rescue 116, que ali se despenhou em 2017, lembrando a todos, em silêncio firme, que o mar é tão generoso quanto implacável.

A torre Martello, imponente, vigiando tudo… As praias… e as três ilhas que se avistam na perfeição — Colt Island, a mais distante e selvagem; Shenick Island, com a sua torre Martello; e St. Patrick’s Island, onde, dizem, atracou S. Patrício.

Por curiosidade fiquei a saber, que o terreno que pisava, Red Island, fora em tempos uma ilha ligada ao continente apenas por uma faixa de terra estreita aquando a maré baixa — fenómeno conhecido como tombolo. Com o tempo, a acumulação de sedimentos e a construção de uma estrada ligaram-na permanentemente à terra firme, transformando-a numa península.

Tempo ainda para uma volta no centro da cidade. Elegante, fresca, plena de vida… A arte e a História continuavam a seguir-me como uma sombra…

O monumento a James Hans Hamilton — erguido entre 1863 e 1865, em memória do antigo deputado e senhorio das terras de Skerries que representou o condado de Dublin por 22 anos — um obelisco de calcário, em estilo georgiano, com placas de mármore que, dizem, contavam a história de quem ali era lembrado, com relatos de inquilinos e apoiantes locais, homenageando aquele que consideravam um amigo generoso e benemérito. Hoje essas placas encontram-se em branco, vamos lá saber porquê.

Mais à frente a deliciosa escultura Embracing Seals, de Paul D’Arcy, junto ao Floraville Park: três focas em tamanho real em calcário português — uma obra que convida a ser tocada e até servindo de assento para os visitantes…

E no caminho, outra escultura de Bríd Ní Rinn — Cormorant ( Corvo-Marinho) que eterniza o perfil característico deste pássaro marinho, tão presente nas rochas da vila.

Ou o cartaz que apela à adopção de uma praia…

Um último relance ao mar onde os pássaros levantam voo lembrando-me que está na hora de eu partir…

English Version

Off I went again to County Fingal…

This time to visit Skerries, a coastal town 30 km from Dublin.

First, there was a short stop in Lusk, because the need for caffeine always speaks louder. Lusk felt like a ghost town — deserted, lifeless, and with little to see. To give you an idea, I had to ask two souls I came across where I might find a coffee, as I couldn’t spot a single sign of one. Perhaps surprised by the question, they pointed me to Lidl…

Willing to follow their directions — basically already going into withdrawal — I came across a pub and didn’t go any further…

I won’t comment on the quality of the coffee, but I loved the pub…

Taking advantage of the stop, I couldn’t resist investigating the tower that stood out on the horizon. As it turns out… it was part of an ecclesiastical complex. Now, as I often say, “behind every beautiful tower, there’s always something to learn”, so off I went to read up on it. The tower in question, standing 27 metres tall, goes by the name of St. Macculin’s Round Tower and was likely built by an early monastic community — like so many other round towers in Ireland, designed to withstand time, Vikings, and the turns of History. Next to it, a 15th-century square bell tower and a 19th-century church complete the trio, giving the place a rather peculiar look. Three different eras sharing the same churchyard, as if the past couldn’t quite fit into just one. And of course, the cemetery, with gravestones worn down by time.

Not sure if it’s down to rivalry, a lack of imagination, or just the saint’s popularity, but there’s another church in town — this time the Catholic one — also named St. MacCullin's Catholic Church. Designed by architect J. J. Robinson and built between 1924 and 1930 in a neo-Romanesque style, it’s one of the newest in the area. The building stands out with its solid-cut granite walls, rounded arch windows, and stained glass by none other than Harry Clarke, one of Ireland’s greats. Inside, there’s a vaulted nave and an altar full of artistic flair.

I couldn’t help noticing the old water pumps dotting the streets and the main square — little reminders of another time.

And so I left Lusk behind, quite happy with what my caffeine cravings had managed to dig up…

Here we go… Onward to Skerries. But first, a stop at Ardgillan Castle — set on a 194-acre estate in Balbriggan, about 6 km from Skerries.

Originally built in 1738 as “Prospect House” by Robert Taylor, the building was extended in the 19th century and ended up with something of a castle-like appearance, though it never lost its Victorian charm. Surrounded by walled gardens — including the magnificent Rose Garden — it also boasts woodland trails, stables, Victorian glasshouses, traditional courtyards (those rural outbuildings so typical of estates like this), and sweeping views out to sea and over the Mourne Mountains, already in Northern Ireland.

Today, it’s a vibrant public space offering guided tours, exhibitions, a tea room housed in the old Cottage — the Brambles Tea Room — and even a playground that, in 2018, received an award: the Pollinator Award, which recognises initiatives that support biodiversity and pollinator protection.

I hadn’t planned to visit the interior of the castle — and even if I had, a sign on the door politely explained that tours were temporarily suspended due to a film being shot there...

Next stop: Skerries Mills. And what a stop! One of those places that at first glance seems merely quaint — with its neatly placed windmills on the horizon — but, as you walk through it, begins to reveal layers of history, ingenuity, and community life.

This unique complex in Ireland — and rare even by European standards — brings together two windmills, a watermill, a former bakery, and everything a small rural ecosystem once required: channels, ponds, vegetable gardens, walking paths, and an energy source that, in its time, powered an entire village. Quite literally.

The original watermill dates back to the 13th century and still operates — fed by a clever system of channels and sluice gates that turn a wooden wheel just like in the old days. A little further up stands the thatched windmill — more modest, with four sails — built atop the remains of an early monastic fort. And at the top of the hill, the Great Windmill rises with its five sails, a commanding and almost theatrical presence over the landscape.

There are guided tours that, according to what they say, explain how all of this worked together — wind and water grinding flour, workers climbing narrow stairs, grains passing through sieves and gears — all the way to the old bakery.

Today, that bakery has been transformed into the Watermill Café, serving freshly baked scones, cakes, soups, and salads, enjoyed either inside or on the terrace overlooking the mills and the cornfields still cultivated around the area.

A craft shop featuring pieces by local creators, a small museum with historical artifacts (including relics from the Tayleur shipwreck of 1854), and a playground awarded the Pollinator Award in 2022 complete this complex. On Saturdays, there’s also a farmers’ market where Skerries gathers around cheeses, breads, and conversations.

Skerries Mills is more than just an open-air museum; it’s a living place — where you can feel the connection between past and present, land and sea, ingenuity and community. And even if you don’t come intending to grind anything, you’ll leave grinding — if not from a meal or a scone with tea, then surely from all the ideas to digest…

I headed towards the seafront to enjoy the rest of the journey. Neither the heavy skies nor the first drops of rain falling would stop me from carrying out my plan — especially since here, rain is always around at some point in the day…

The harbour, with boats gently swaying, seemed to be dozing between tides. The quay and its lighthouse at the tip… Seagulls, unfazed by the light drizzle, swooped low or perched on the walls, completing the scene alongside colourful houses, cafés with open doors, the Sailing Club where boats came and went to the sea, and the seaside promenade which, as if the views weren’t enough, serves as an open-air gallery with sculptures scattered along the route and informative panels.

Among them, the Tidy Towns Sculpture, created by Shane Holland and commissioned to celebrate Skerries’ 2016 National Tidy Towns award; the sculpture Terns, by Irish artist Bríd Ní Rinn; and an informational panel about the Mourne Mountains, visible from there on clear days.

In Red Island Square stands the Sea Pole Memorial — an old rescue mast transformed into a moving monument, bearing the names of over 260 people and ships lost at sea through the centuries. Inaugurated in 2013 by President Michael D. Higgins, it also honours the crew of Rescue 116 helicopter, which crashed there in 2017, silently reminding everyone that the sea is as generous as it is relentless.

The imposing Martello Tower watches over everything… the beaches… and the three islands perfectly visible — Colt Island, the most distant and wild; Shenick Island, with its own Martello Tower; and St. Patrick’s Island, where, it is said, St. Patrick once landed.

Out of curiosity, I learned that the land I was standing on, Red Island, was once an island connected to the mainland only by a narrow strip of land at low tide — a phenomenon known as a tombolo. Over time, sediment buildup and the construction of a road permanently linked it to the mainland, turning it into a peninsula.

There was still time for a stroll through the town centre. Elegant, fresh, full of life… Art and History continued to follow me like a shadow…

The monument to James Hans Hamilton — erected between 1863 and 1865 in memory of the former MP and landlord of Skerries’ lands who represented County Dublin for 22 years — is a limestone obelisk in Georgian style, with marble plaques that, it is said, once told the story of the man being honoured, including accounts from tenants and local supporters, celebrating someone they considered a generous and benevolent friend. Today, those plaques are blank — let’s find out why.

Further along is the delightful sculpture Embracing Seals by Paul D’Arcy, near Floraville Park: three life-sized seals carved from Portuguese limestone — a work that invites touch and even serves as a seat for visitors…

And along the way, another sculpture by Bríd Ní Rinn — Cormorant — which immortalises the distinctive profile of this seabird, so common on the village’s rocks.

Or the poster urging people to adopt a beach…

One last glance at the sea, where the birds take flight, reminding me it’s time to leave…

Comentários