Wexford: a cidade e mais além / Wexford: the city and beyond

- luaemp

- 14 de nov. de 2025

- 11 min de leitura

(Followed by the English version)

Se bem se lembram, o primeiro destino no condado de Wexford foi Ferns, uma vila na qual pouco esperava encontrar e acabei mergulhada nos enredos da história como se desensarilhasse uma meada.

As expectativas estavam elevadas quando seguimos para Wexford, a capital administrativa deste condado.

Estacionamos no parque da Igreja da Imaculada Conceição e S. João, mais conhecida como Rowe Street Church — a irmã gémea da Bride Street, oficialmente denominada por Igreja da Assunção.

Chamam-lhes “gémeas” porque ambas foram construídas praticamente ao mesmo tempo, na segunda metade do século XIX, assinadas pelo mesmo arquitecto — Richard Pierce — seguindo o mesmo estilo neogótico e até com a mesma lógica de grandeza arquitectónica: arcos em ogiva, torre imponente de vários andares e um pináculo que parece apontar-nos o caminho do céu. Construída em arenito vermelho local e granito de Wicklow, a igreja não se limita a ser um edifício de culto — é também uma afirmação estética de uma comunidade que, mesmo após os anos da Grande Fome, quis dar forma grandiosa à sua fé.

(Igreja da Imaculada Conceição e S. João)

(Igreja da Assunção)

“Começamos bem”— pensei eu…

À medida que nos fomos aproximando da Main Street, um pequeno recanto ajardinado embelezava os já bonitos resquícios das muralhas medievais da cidade. Estas foram construídas pelos colonos anglo-normandos no final do século XII para proteger a cidade recém-estabelecida. Wexford foi uma das primeiras cidades a ser murada na Irlanda, e as muralhas desempenharam um papel crucial na defesa contra ataques durante os séculos XIII e XIV.

A chuva teve a sua meia hora de fama, mas não nos demoveu de continuar a visita. Já nos habituamos à mudança de humor do tempo e sabemos olhar o céu e perceber o que vem a seguir.

Não muito longe a Abadia Selskar, começava insinuar-se.

A Selskar Abbey, também conhecida como o Priorado de S. Pedro e S. Paulo, foi fundada por volta de 1190 como um priorado agostiniano. O nome "Selskar" deriva do norueguês antigo "sel-skar", significando "rocha das focas" — onde é que já ouvi isto?! A abadia desempenhou um papel importantíssimo na história medieval de Wexford e é um dos principais marcos anglo-normandos da cidade.

Embora a maior parte da estrutura original tenha sido destruída ao longo dos séculos, ainda restam vestígios da igreja e da torre.

A área ao redor da abadia transborda igualmente de história: a muralha e uma das portas da cidade, a antiga prisão de Wexford (Wexford Gaol) — construída em 1812 e hoje parcialmente transformada no Wexford Gaol Heritage Centre, onde os visitantes podem conhecer a vida na prisão nos séculos XIX e XX — e o Jardim Republicano da Memória, situado atrás da antiga prisão — criado para homenagear os republicanos irlandeses que perderam a vida na luta pela independência.

Entre eles destacam-se James Parle, John Creane e Patrick Hogan, executados a 13 de março de 1923, durante a Guerra Civil Irlandesa. Ali, placas comemorativas marcam o local preciso da execução destes homens, e uma árvore especial, com o nome Liberdade, plantada para comemorar o bicentenário da Rebelião de 1798.

Seguimos pela longa Rua Principal, cuja extensão é maioritariamente pedonal. Junto à Dunnes, uma sequência de painéis pintados narra a história da cidade.

Na Praça Redmond, ergue-se um obelisco, um monumento consagrado a perpetuar a memória da influente família Redmond, em especial John Edward Redmond, que representou Wexford no Parlamento britânico no século XIX e cujo nome ficou para sempre ligado ao desenvolvimento e identidade da cidade. A inscrição gravada no pedestal resume bem esse laço: “My heart is with the city of Wexford. Nothing can extinguish that love but the cold soil of the grave.”

Por esta altura, a chuva requeria abrigo e nem hesitamos em nos enfiar no Green Acres — um edifício classificado, datado de 1894 que hoje abriga um restaurante, café, uma loja gourmet, outra de vinhos e uma galeria de arte — esta última o nosso refúgio da pequena intempérie que resolveu instalar-se.

Soube-nos bem pousar os olhos nas peças expostas, respirar o silêncio do ventre deste edifício com história, de apreciar a cidade de cima, numa outra perspectiva.

Não foi preciso muito para a chuva passar. Voltando a Main Street, deleitamo-nos com pequenos detalhes, montras bem concebidas, e o bulício da cidade.

Ao longe insinuam-se as ruínas da antiga Igreja de S. Patrício (Saint Patrick’s Church), uma das cinco paróquias que existiam dentro das muralhas medievais de Wexford. Hoje resta apenas parte da estrutura, mas ainda assim é considerada a ruína de igreja medieval mais bem preservada da cidade, rivalizando até com a famosa Selskar Abbey.

O pequeno adro que a envolve, voltado para a Praça de S. Patrício (Patrick’s Square), dá-lhe uma atmosfera quase esquecida, como se a memória da Wexford medieval ainda resistisse entre pedras gastas e silêncios seculares.

Não muito longe, numa outra praça, a The Bullring, ergue-se a estátua de The Pikeman, em memória dos insurgentes da Rebelião de 1798. O pikeman representa os camponeses e cidadãos que se levantaram armados com piques (lanças compridas de madeira com ponta metálica) contra o domínio britânico, simbolizando a coragem e a resistência do povo de Wexford. A praça circular que a abraça convida os visitantes a reflectir sobre a história turbulenta da cidade, misturando passado e presente num mesmo espaço urbano.

Seguimos com passo lento, calcorreando a High Street onde se ergue a National Opera House, inaugurada em 2008 no local do antigo Theatre Royal. Projectada por Keith Williams, é o primeiro edifício de ópera construído de raiz na Irlanda tendo recebido vários prémios de arquitectura. O seu interior combina linhas modernas com uma acústica de excelência, distribuída entre o grande auditório O’Reilly e o mais íntimo Jerome Hynes Theatre.

Durante todo o ano, este edifício encarna um verdadeiro espaço cultural aberto à música, ao teatro e às artes em geral. Além disso, acolhe, todos os anos, entre finais de Outubro e Novembro, o Wexford Festival Opera, um evento de renome internacional que transforma a cidade num palco vivo, entre óperas, recitais, concertos e encontros culturais.

Tempo de rumar a outras paragens… no caminho, cruzámos o rio Slaney e a sua ponte histórica, a Wexford Bridge.

A primeira ponte neste local foi construída em 1795, pelo engenheiro americano Lemuel Cox, em madeira de carvalho, com cerca de 474 metros de comprimento. Ao longo do tempo, esta ponte tornou-se palco de episódios marcantes, incluindo acontecimentos ligados à Rebelião de 1798, quando rebeldes irlandeses foram executados nas suas tábuas.

Em 1866, a estrutura de madeira foi substituída por uma ponte de pedra, mais resistente. A versão actual, foi inaugurada em 1959, projectada para suportar o crescente tráfego rodoviário e continuar a servir como elo vital da cidade.

Despedi-me da cidade, ali mesmo, no meio da ponte, olhando a mansidão do rio e os barcos que o enfeitavam. Muita coisa ficou por ver, muitas ruas por calcorrear. Quem sabe um dia volto… Por agora, havia mais um sítio que queriamos pisar.

E para lá nos dirigimos…

A praia de Curracloe, um areal dourado e finíssimo que parece não ter fim, abraçado por dunas onduladas e pelo ritmo constante do Atlântico.

Não é apenas um refúgio para caminhadas intermináveis ou para os banhos de verão — foi também palco de cinema. Aqui, mais concretamente em Ballinesker, parte desta mesma extensão de areia, que Steven Spielberg filmou, em 1997, as intensas cenas do desembarque na Normandia em Saving Private Ryan. Desde então, Curracloe tornou-se não só um destino de lazer mas também um lugar de memória, onde a beleza natural se cruza com a história evocada pela sétima arte.

Apesar da nortada, passeamos sob aquela areia fina, rara de encontrar nas praias daqui. O Atlântico estava agitado, mas mesmo assim, havia gente afoita, que por ele entrava…

Deu para perceber a extensão do areal, a beleza das dunas preservadas e até para ter um ou outro pensamento filosófico sobre a nossa pequenez, quais grãos de areia no imenso Universo e sobre a passagem do tempo que, invariavelmente, nos reporta à finitude — nossa e das coisas.

Partimos deste condado de Wexford com a sensação de que ainda havia muito por descobrir, mas é assim que devem ser as viagens: deixar sempre um motivo para voltar.

English Version

If you remember, our first destination in County Wexford was Ferns, a village where I had expected little and yet found myself immersed in the twists and turns of history, as if untangling a skein. Expectations were high as we made our way to Wexford, the administrative capital of the county.

We parked near the Church of the Immaculate Conception and St. John, better known as Rowe Street Church — the twin of Bride Street Church, officially called the Church of the Assumption. They are called “twins” because both were built almost simultaneously, in the second half of the nineteenth century, designed by the same architect — Richard Pierce — following the same neo-Gothic style and even the same logic of architectural grandeur: pointed arches, an imposing multi-storey tower, and a spire that seems to point the way to heaven. Constructed from local red sandstone and Wicklow granite, the church is not merely a place of worship — it is also an aesthetic statement by a community that, even after the years of the Great Famine, sought to give grand form to their faith.

(Church of the Immaculate Conception and St. John)

(Church of the Assumption)

“Off to a good start,” I thought…

As we drew closer to Main Street, a small landscaped corner adorned the already beautiful remnants of the city’s medieval walls. These had been built by the Anglo-Norman settlers at the end of the twelfth century to protect the newly established town. Wexford was one of the first walled towns in Ireland, and the walls played a crucial role in defending against attacks during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.

The rain had its fifteen minutes of fame, but it did not deter us from continuing the visit. We had already grown accustomed to the changeable moods of the weather and know how to read the sky to see what comes next.

Not far away, Selskar Abbey began to reveal itself.

Selskar Abbey, also known as the Priory of St. Peter and St. Paul, was founded around 1190 as an Augustinian priory. The name “Selskar” comes from the Old Norse “sel-skar,” meaning “seal rock” — where have I heard that before?! The abbey played a very important role in Wexford’s medieval history and is one of the city’s main Anglo-Norman landmarks.

Although most of the original structure has been destroyed over the centuries, traces of the church and tower still remain. The area surrounding the abbey is equally steeped in history: the city wall and one of its gates, the old Wexford Gaol — built in 1812 and now partially transformed into the Wexford Gaol Heritage Centre, where visitors can learn about prison life in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries — and the Republican Memorial Garden, located behind the old gaol, created to honour the Irish republicans who lost their lives in the struggle for independence.

Among them are James Parle, John Creane, and Patrick Hogan, executed on 13 March 1923 during the Irish Civil War. Here, commemorative plaques mark the exact site of their execution, and a special tree, named Liberty, was planted to celebrate the bicentenary of the 1798 Rebellion.

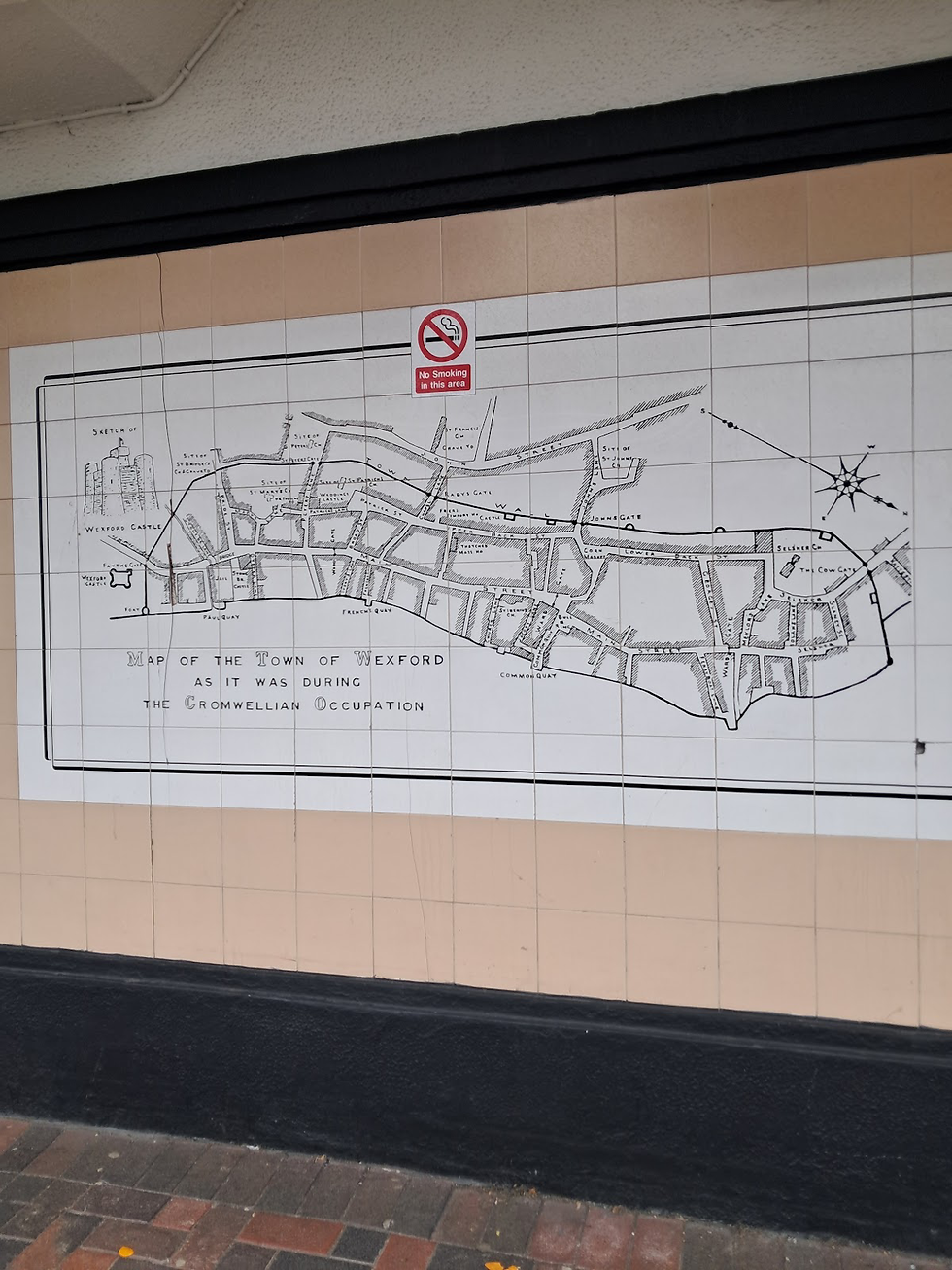

We continued along the long Main Street, most of which is pedestrianised. Beside Dunnes, a series of painted panels narrates the history of the city.

In Redmond Square stands an obelisk, a monument dedicated to perpetuating the memory of the influential Redmond family, especially John Edward Redmond, who represented Wexford in the British Parliament in the nineteenth century and whose name became forever linked to the development and identity of the city. The inscription on the pedestal perfectly captures this connection: “My heart is with the city of Wexford. Nothing can extinguish that love but the cold soil of the grave.”

By this time, the rain called for shelter, and we didn’t hesitate to slip into Green Acres — a listed building dating from 1894, which today houses a restaurant, a café, a gourmet shop, a wine store, and an art gallery — the latter becoming our refuge from the brief downpour.

It felt good to rest our eyes on the exhibited pieces, to breathe in the silence of the heart of this historic building, and to appreciate the city from above, from a different perspective.

It didn’t take long for the rain to pass. Returning to Main Street, we delighted in the small details, the well-designed shop windows, and the bustle of the city.

In the distance, the ruins of the old Saint Patrick’s Church, one of the five parishes that once existed within Wexford’s medieval walls, began to appear. Today, only part of the structure remains, yet it is still considered the best-preserved medieval church ruin in the city, rivalled even by the famous Selskar Abbey.

The small churchyard that surrounds it, facing Patrick’s Square, gives it an almost forgotten atmosphere, as if the memory of medieval Wexford still lingers among worn stones and centuries-old silences.

Not far away, in another square, The Bullring, stands the statue of The Pikeman, in memory of the insurgents of the 1798 Rebellion. The pikeman represents the peasants and citizens who rose up armed with pikes (long wooden spears with metal tips) against British rule, symbolising the courage and resistance of the people of Wexford. The circular square that embraces it invites visitors to reflect on the city’s turbulent history, blending past and present in the same urban space.

We continued at a leisurely pace along High Street, where the National Opera House rises, inaugurated in 2008 on the site of the former Theatre Royal. Designed by Keith Williams, it is the first purpose-built opera house in Ireland and has received several architectural awards. Its interior combines modern lines with outstanding acoustics, distributed between the large O’Reilly Auditorium and the more intimate Jerome Hynes Theatre.

Throughout the year, this building embodies a true cultural space open to music, theatre, and the arts in general. In addition, every year, from late October to November, it hosts the Wexford Festival Opera, an internationally renowned event that transforms the city into a living stage, featuring operas, recitals, concerts, and cultural gatherings.

Time to head to other destinations… along the way, we crossed the River Slaney and its historic Wexford Bridge.

The first bridge on this site was built in 1795 by the American engineer Lemuel Cox, made of oak timber and approximately 474 metres long. Over time, this bridge became the stage for significant events, including those related to the 1798 Rebellion, when Irish rebels were executed upon its planks.

In 1866, the wooden structure was replaced by a more durable stone bridge. The current version was inaugurated in 1959, designed to accommodate increasing road traffic while continuing to serve as a vital link for the city.

I said goodbye to the city right there, in the middle of the bridge, watching the calm river and the boats that adorned it. There was still much left to see, many streets left to wander. Who knows, perhaps one day I’ll return… For now, there was one more place we wanted to set foot on.

And so we headed there…

Curracloe Beach, a golden, fine stretch of sand that seems endless, embraced by rolling dunes and the steady rhythm of the Atlantic.

It is not only a refuge for endless walks or summer swims — it has also been a film location. Here, more specifically in Ballinesker, part of the same stretch of sand, Steven Spielberg filmed the intense Normandy landing scenes in Saving Private Ryan in 1997. Since then, Curracloe has become not only a leisure destination but also a place of memory, where natural beauty intersects with the history evoked by the seventh art.

Despite the northerly wind, we walked along that fine sand, rare to find on beaches around here. The Atlantic was rough, yet there were still daring souls venturing into it…

We could appreciate the vastness of the beach, the beauty of the preserved dunes, and even have a few philosophical thoughts about our own smallness, like grains of sand in the immense Universe, and about the passage of time, which inevitably reminds us of our finitude — both ours and that of things.

We left County Wexford with the feeling that there was still much to discover, but that is how journeys should be: always leaving a reason to return.

Comentários